![Plimpton party 1963 A cocktail party at George Plimpton’s apartment in 1963; Plimpton is seated at left. [Photo by Cornell Capa/Magnum Photos/NYT]](../../../../images/2008/11/16/books/carter-2-650.jpg)

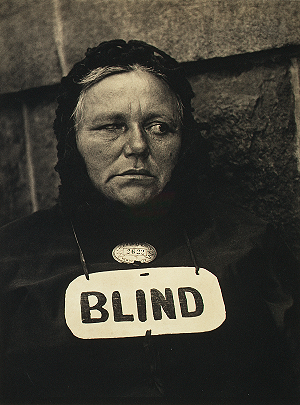

A cocktail party at George Plimpton’s apartment in 1963; Plimpton is seated at left. [Photo by Cornell Capa/Magnum Photos/NYT]

Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter wrote a long essay in the NYT Book Review based on George, Being George, a new oral history of the Paper Lion. Following a recent publishing trend that seems to hark back to the 18th century, the book has a whopper of a subtitle: “George Plimpton’s Life as Told, Admired, Deplored, and Envied by 200 Friends, Relatives, Lovers, Acquaintances, Rivals — and a Few Unappreciative Observers.”

Here’s a passage about the salad days of The Paris Review:

Like so many other smart young men of his age and wherewithal, George followed the example of the Lost Generation and headed to Paris. Back at home, there were headlines about the Korean War and Joseph McCarthy. On the Left Bank, says Bill Becker, a Harvard classmate: “We were living like kings. In Paris, on the black market in the mid-1950s, you could exchange a dollar for 600 francs.” Hotel rooms cost 300 francs a night; a decent meal with a bottle of Beaujolais was a little more than half that. Styron came. So did Terry Southern and James Baldwin, and Robert Silvers and Peter Duchin lived on a barge docked near the Place de l’Alma. A number of this new generation were secretly recruited into the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency — the cold-war offspring of the wartime O.S.S. (nicknamed Oh So Social).

It is a common misperception that George founded The Paris Review. He did not. Like so many other things in this gilded life, it was given to him — in this case by its creators Matthiessen, a classmate at St. Bernard’s, and Harold Humes, known as Doc, who asked him to be its editor. Arguably though, without him the magazine, like so many similar small journals, would have sputtered and died after a few issues. The first number, with a minimal circulation in England, the United States and Europe, established the DNA for what it would remain for the next half-century. Donald Hall, who later became poet laureate, served as poetry editor. Styron, already celebrated for “Lie Down in Darkness,”wrote the introduction. And the first of volumes of Paris Review interviews kicked off with one with E. M. Forster, the man who, it was said, became more famous with every book he didn’t write. George had made the connection with Forster at Cambridge. And Andrew Leggatt, a former classmate, says, “It was typical of George’s luck, wasn’t it, that he should have known personally such a great literary figure from the past who would be prepared to give him the kind of interview that would subsequently become a classic.”

I am reliably informed that little magazines comprise four elements: shabby, cramped quarters; meager wages; attractive interns of independent means; and boundless enthusiasm. They are also excellent excuses for throwing parties. In Paris, the canteen was the Café le Tournon, near the magazine’s tiny office on the rue Garancière. Friends say George lived a particularly elastic Left Bank/Right Bank existence, editing during the day followed by drinks at the bar of the Ritz or the Crillon. When he relocated the review to New York, he brought his social-engineering skills with him. He held fund-raising “Revels” at bohemian palaces like the Village Gate and later at his home at 541 East 72nd Street, which doubled as living accommodation for him and his family and offices for the magazine. A consummate host, he shouted a guest’s name above a crowd as a form of welcome. “Bring a pretty girl,” he would tell interns like David Michaelis, who worked at the magazine in the mid-’70s. “He always said it when he invited me to a party, and I heard him say it to other young men later. . . . It was like an Irwin Shaw story, that lovely midcentury feeling.”

And indeed, there were all manner of interesting men and interesting and pretty young women. Talese’s Esquire article on George openswith one of his parties, and on a night when Jackie Kennedy came by. And there is that famous Life photograph [above] by Cornell Capa, taken the same year, of a party at George’s that is as much a midcentury New York period piece as Billy Wilder’s films “The Seven Year Itch” or “The Apartment.” Throughout the vast living room are women in pinch-waist cocktail dresses and men in smart suits with thin ties. In the picture you can spot Capote, Styron and Vidal, as well as Ralph Ellison, Frank and Eleanor Perry, Mario Puzo, Arthur Penn and Arthur Kopit. At one of George’s parties, Mailer and Humes got into a fight. “I remember George seizing me from behind in an iron grip that I could not get out of,” Mailer says. “Because he was around so many people, boxers, football players, who were stronger than him, he never bothered to discuss his strength. But I remember thinking, ‘God damn it, that guy is strong.’ ”

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in