Frank Shay closed his Greenwich Village bookshop during the slow summer months so he could peddle books on Cape Cod using a Ford truck outfitted as a mobile “bookwagon.” [Source: Harry Ransom Center/ University of Texas]

- The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door: A Portal to Bohemia, 1920-1925

In the early 1920s, noteworthy visitors to Frank Shay’s bookshop at 4 Christopher Street began autographing the narrow door that opened onto the shop’s office. Signed by 242 artists, writers, publishers, and other notable habitués of Greenwich Village, this unusual artifact is now housed at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A literal portal to the past, the door reveals the rich mix of innovators—from anarchist poets to major commercial publishers—that defined this slice of Bohemia from 1920 to 1925. This exhibition reconstructs the bookshop and its community. The door is not accompanied by an archive of the bookshop, so this project seeks to create a virtual “archive” on the web. Artifacts gathered from across the Ransom Center’s collections provide audiences with documentation of the shop’s operations and the lives and careers of its customers. This is an ongoing project: we hope that audience participation will enrich the project with further information. - Essay — A Portal to 1920s Greenwich Village — by Jennifer Schuessler - NYTimes.com 090111

Jennifer Schuessler: “Three years ago, a most unusual artifact resurfaced in a storage space of the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. It was a narrow pine door, edged in bright blue paint and covered with some 242 signatures, many of them smudged or adorned with elaborate doodles. It turned out to be from Frank Shay’s bookstore, a popular Greenwich Village establishment that opened for business at 4 Christopher Street in 1920. It was removed by the manager when the shop closed in 1925 and bought by the Ransom Center in 1960, after a dealer spotted an ad in the Saturday Review asking, “Want a door?” A 1972 article in the Ransom Center’s journal identified 50 people behind the signatures before the door fell back into obscurity, as forgotten as most of the characters who had scratched their names on its surface. But now, a new exhibition, “The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door: A Portal to Bohemia, 1920-1925,” identifies some 140 additional signatures…”

- The Mechanic Muse — From Scroll to Screen - NYTimes.com 090211

Lev Grossman: “Something very important and very weird is happening to the book right now: It’s shedding its papery corpus and transmigrating into a bodiless digital form, right before our eyes. We’re witnessing the bibliographical equivalent of the rapture. If anything we may be lowballing the weirdness of it all. The last time a change of this magnitude occurred was circa 1450, when Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type. But if you go back further there’s a more helpful precedent for what’s going on. Starting in the first century A.D., Western readers discarded the scroll in favor of the codex — the bound book as we know it today. | The codex … created a very different reading experience… you could jump to any point in a text instantly, nonlinearly. You could flip back and forth between two pages and even study them both at once. You could cross-check passages and compare them… You could skim if you were bored, and jump back to reread your favorite parts. “

- Believing Is Seeing - By Errol Morris - Book Review - NYTimes.com 090111

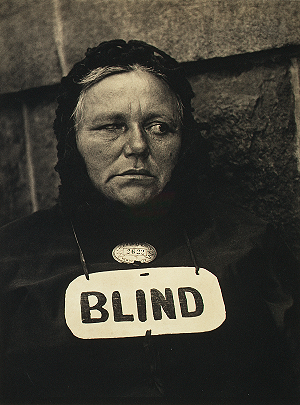

One of the first things we learn in “Believing Is Seeing” is that its author, the filmmaker Errol Morris, has limited sight in one eye and lacks normal stereoscopic vision — “My fault,” he writes, for refusing to wear an eye patch after being treated for strabismus in childhood. It’s hard to think of another writer who so neatly embodies the theme of his own book. “Believing Is Seeing” is about the limitations of vision, and about the inevitable idiosyncrasies and distortions involved in the act of looking — in particular, looking at photographs.

- Daniel Yergin Examines America’s ‘Quest’ For Energy : NPR

The ad is part of an intensifying debate over hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking” — the process energy companies use to get a certain kind of natural gas out of the ground. Fracking is also one of the many subjects energy expert Daniel Yergin covers in his new book, The Quest. Yergin tells NPR’s David Greene that the type of natural gas obtained through fracking, the gas found in shale, only recently became a serious energy source for the U.S. [Includes link to book excerpt]

- Jon Hendricks: The Father Of Vocalese At 90 : NPR 091611

Jon Hendricks turned 90 on Friday. The singer and lyricist is best known for his work with Lambert, Hendricks and Ross in the 1950s, putting words to jazz — including insanely complex vocal arrangements of instrumental solos. One of Hendricks’ favorite anecdotes involves a party where the wives of composer Jerome Kern and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II had a little dispute over who wrote “Old Man River.” “Beg your pardon. Your husband wrote, ‘Da da da da.’ My husband wrote ‘Old Man River,’ ” Hendricks recalls, laughing. “And that’s a good illustration of how the lyric brings the song out like a flower blossoms. It’s the lyric that makes the song.”

Jon Hendricks writes his own songs — words and music — and is also a critically acclaimed jazz singer. But he’s best known for fashioning lyrics to the big-band arrangements of Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Woody Herman — not just the melodies, but all of the parts, down to the most technically demanding solos. - How Can Parents Navigate Children’s TV Shows? : NPR 091511

Michele Norris speaks with Dr. Dimitri Christakis about how parents can navigate the world of children’s TV programs. A new study done at the University of Virginia with a group of 4 year olds found those who’d watched the fast-paced cartoon SpongeBob SquarePants performed worse on mental function tests than their peers who watched the slower-paced cartoon Calliou or who simply spent their time drawing. Christakis says young children’s brains get over-stimulated by the faster-paced programs, and urges parents to think about what kind of television-watching experience they want their children to have.

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

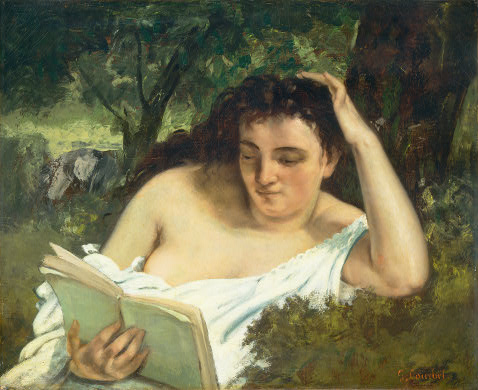

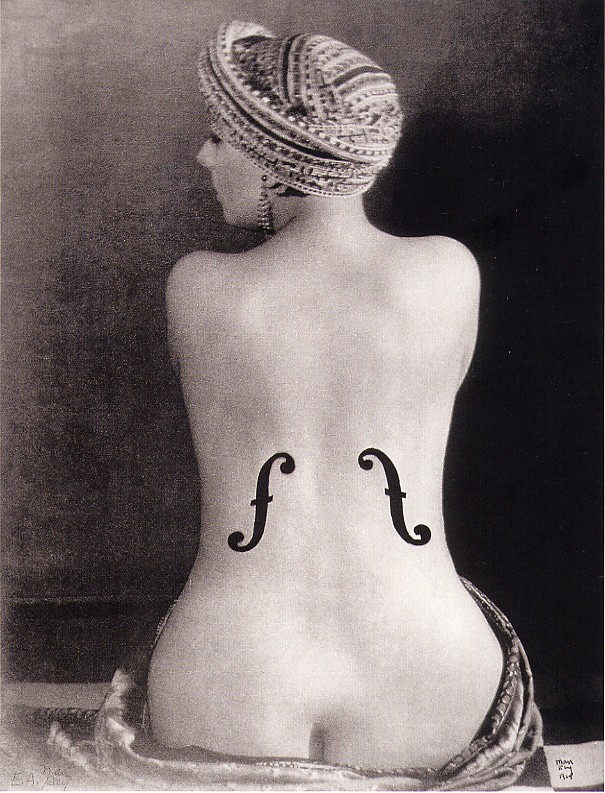

The legendary Kiki of Montparnasse posed for Man Ray’s

The legendary Kiki of Montparnasse posed for Man Ray’s

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

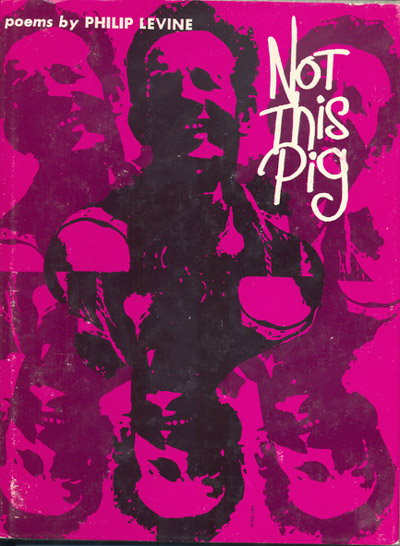

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

![grant_wood_parson_weems_fable_200px Grant Wood. Parson Weem’s’ Fable. 1939. Amon Carter Museum, Forth Worth.. Steven Biel describes the painting: “Parson Weems, imitating Charles Willson Peale’s pose in The Artist in His Museum (1822), opens a red velvet curtain on the legendary scene: Augustine Washington, elegant in crimson coat, white ruffle, tan breeches, silver-buckled pumps, and green tricornered hat, grasps in his right hand the slim trunk of the bent cherry tree. A row of cherries dangles from the perfectly rounded treetop, mirroring the very cherry-like fringe of the Parson’s curtain. Augustine’s outstretched left palm and furrowed brow signal a serious inquiry. His son George, boyish in stature and dress—coatless, with sky-blue breeches and petite buckled pumps—is manly in his expression. In fact, his white-wigged head is that of Gilbert Stuart’s portrait and the dollar bill. He points with his right hand to the hatchet in his left. Wood chips lie in the circle of soil at the base of the tree, its lower trunk smoothly incised and poised to split off. In the background, a well-dressed slave couple harvests the fruit of a second tree.” [Alt Text Source: Common-Place/ http://www.common-place.org/vol-06/no-04/biel/ ]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2011/08/grant_wood_parson_weems_fable_200px.jpg)