Les Misérables is one of those roman á fleuvre (a phrase cribbed from Walter Benjamin, who knew all about the genre after translating Proust) that descend through treacherous eddies and backwaters before finally reaching the sea. It takes a stalwart, even obsessed, reader to cover its vast distance in one passage. I started the book at Christmas, 2005, and was cast ashore before I mastered the 19th-century book structure and character names. I picked it up again in the summer of 2006 and its gathering narrative current swept me along until I hit slack water in the dog days of August: volume IV, book 7, chapters 1-3 (I will henceforth document such text locations as IV.7.1-3). It is a long, stultifying discourse on slang, which probably is interesting in its own righ, but it differs so much in tone from the narrative that precedes and follows that it feels like a different river. I put the book down for more than a year.

Les Misérables is one of those roman á fleuvre (a phrase cribbed from Walter Benjamin, who knew all about the genre after translating Proust) that descend through treacherous eddies and backwaters before finally reaching the sea. It takes a stalwart, even obsessed, reader to cover its vast distance in one passage. I started the book at Christmas, 2005, and was cast ashore before I mastered the 19th-century book structure and character names. I picked it up again in the summer of 2006 and its gathering narrative current swept me along until I hit slack water in the dog days of August: volume IV, book 7, chapters 1-3 (I will henceforth document such text locations as IV.7.1-3). It is a long, stultifying discourse on slang, which probably is interesting in its own righ, but it differs so much in tone from the narrative that precedes and follows that it feels like a different river. I put the book down for more than a year.

Hoping to hang onto that indulgent, elegiac feeling associated with “summer reading,” I picked up Les Mis again two nights ago. I did, literally, pick up a vintage copy of the Modern Library edition, and I could put my finger directly on the didactic section that stopped me last summer. But I read the book by listening to an audio recording produced by the Library of Congress, and I couldn’t remember which cassette track was last read. I re-read a hundred pages over several hours of listening, and IV.7.1-3 is still a ways downstream. In the mean time, I’m remembering the characters as I meet them again.

That brings me to Gavroche, the gaman who steals the show in IV.6.1-3. Re-reading it, I realized how Gavroche was Huck Finn’s pre-cursor (metaphorically and literally) . He is Huck Finn with a dash of Jessie James and Frantz Fanon thrown in for good measure!

In IV.6.1, Gavroche is making his way to Place Bastille when he finds two younger waifs who have been abandoned to the streets of Paris after their “mother” was arrested. The reader knows, but Gavroche does not, that the boys are actually his long-lost brothers. He takes them under his wing. This scene, which expresses a particular French passion for good bread (and animated language), unfolds somewhere on Rue Saint-Antoine:

As they were passing one of these heavy grated lattices,

which indicate a baker’s shop, for bread is put behind

bars like gold, Gavroche turned round:-“Ah, by the way, brats, have we dined?”

“Monsieur,” replied the elder, “we have had nothing to eat since

this morning.”“So you have neither father nor mother?” resumed Gavroche majestically.

“Excuse us, sir, we have a papa and a mamma, but we don’t know

where they are.”“Sometimes that’s better than knowing where they are,” said Gavroche,

who was a thinker.“We have been wandering about these two hours,” continued the elder,

“we have hunted for things at the corners of the streets, but we

have found nothing.”“I know,” ejaculated Gavroche, “it’s the dogs who eat everything.”

He went on, after a pause:-

“Ah! we have lost our authors. We don’t know what we have done

with them. This should not be, gamins. It’s stupid to let old people

stray off like that. Come now! we must have a snooze all the same.”However, he asked them no questions. What was more simple than

that they should have no dwelling place!The elder of the two children, who had almost entirely recovered

the prompt heedlessness of childhood, uttered this exclamation:-“It’s queer, all the same. Mamma told us that she would take us

to get a blessed spray on Palm Sunday.”“Bosh,” said Gavroche.

“Mamma,” resumed the elder, “is a lady who lives with Mamselle Miss.”

“Tanflute!” retorted Gavroche.

Meanwhile he had halted, and for the last two minutes he had been

feeling and fumbling in all sorts of nooks which his rags contained.At last he tossed his head with an air intended to be merely satisfied,

but which was triumphant, in reality.“Let us be calm, young ‘uns. Here’s supper for three.”

And from one of his pockets he drew forth a sou.

Without allowing the two urchins time for amazement, he pushed

both of them before him into the baker’s shop, and flung his sou

on the counter, crying:-“Boy! five centimes’ worth of bread.”

The baker, who was the proprietor in person, took up a loaf and a knife.

“In three pieces, my boy!” went on Gavroche.

And he added with dignity:-

“There are three of us.”

And seeing that the baker, after scrutinizing the three customers,

had taken down a black loaf, he thrust his finger far up his nose

with an inhalation as imperious as though he had had a pinch of the

great Frederick’s snuff on the tip of his thumb, and hurled this

indignant apostrophe full in the baker’s face:-“Keksekca?”

Those of our readers who might be tempted to espy in this

interpellation of Gavroche’s to the baker a Russian or a Polish word,

or one of those savage cries which the Yoways and the Botocudos hurl

at each other from bank to bank of a river, athwart the solitudes,

are warned that it is a word which they [our readers] utter every day,

and which takes the place of the phrase: “Qu’est-ce que c’est

que cela?” The baker understood perfectly, and replied:-“Well! It’s bread, and very good bread of the second quality.”

“You mean larton brutal [black bread]!” retorted Gavroche,

calmly and coldly disdainful. “White bread, boy! white bread

[larton savonne]! I’m standing treat.”The baker could not repress a smile, and as he cut the white bread

he surveyed them in a compassionate way which shocked Gavroche.“Come, now, baker’s boy!” said he, “what are you taking our measure

like that for?”All three of them placed end to end would have hardly made a measure.

When the bread was cut, the baker threw the sou into his drawer,

and Gavroche said to the two children:-“Grub away.”

The little boys stared at him in surprise.

Gavroche began to laugh.

“Ah! hullo, that’s so! they don’t understand yet, they’re too small.”

And he repeated:-

“Eat away.”

At the same time, he held out a piece of bread to each of them.

And thinking that the elder, who seemed to him the more worthy

of his conversation, deserved some special encouragement and ought

to be relieved from all hesitation to satisfy his appetite, he added,

as he handed him the largest share:-“Ram that into your muzzle.”

One piece was smaller than the others; he kept this for himself.

The poor children, including Gavroche, were famished.

As they tore their bread apart in big mouthfuls, they blocked up

the shop of the baker, who, now that they had paid their money,

looked angrily at them.“Let’s go into the street again,” said Gavroche.

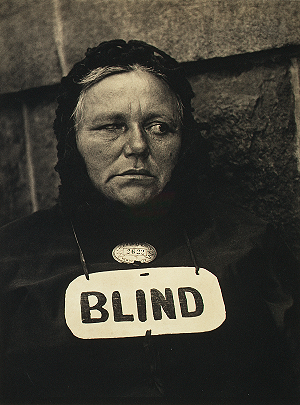

[A Note on Sources: This text comes from the Project Gutenberg etext of Les Misérables, a 19th-century translation in the public domain. I will have much more to say about Project Gutenberg, a priceless cultural treasure for all readers and flaneurs, be ye blind or not.]

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

Pingback: a blind flaneur

Pingback: a blind flaneur

Pingback: a blind flaneur

Pingback: a blind flaneur