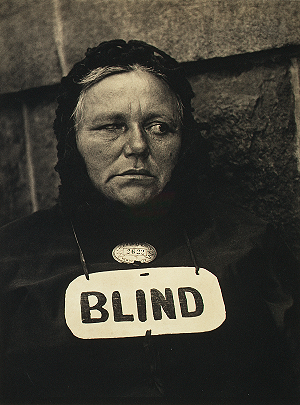

Paul Strand. Blind. 1916. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I want to find new ways to talk about accessibility to engage people who would not otherwise consider that it pertains to them. When I talk about accessibility it doesn’t mean whether or not there is wi-fi at Starbuck’s. It also doesn’t mean the larger context of accessibility for people with disabilities – whether or not there are wheelchair ramps or curb cuts. Those are examples of architectural accessibility. I am talking specifically about access to information and information technologies. I believe that what I will try to achieve in this discussion will relate to other, larger contexts in which we talk about accessibility. Ultimately, I want to talk about accessibility in terms of culture and cultural production.

This image by Paul Strand is my first milestone in talking about accessibility in terms of culture. It has haunted me ever since I first confronted it in the Paul Strand retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1990. The print is in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It has haunted me for several reasons. The first and most obvious reason is the sign that hangs around the woman’s neck. This is a photograph of a blind beggar taken on the street in New York City. As a cultural artifact, there are a number of interesting things about it. Just above the sign that pronounces the woman to be blind is a small pin with a number on it. That is her license number for begging. At the time, in the heyday of the Progressive Era, New York City required beggars to be licensed. It was an approach to managing society’s marginalized people by controlling them. If you wanted to beg on the street, you had to be certified. It’s not clear from the image’s historical documentation whether the city or the beggar herself hung the stigmatizing placard around her neck. To my eye, and particularly to how I remember the image, the placard and certification number are one and the same sign. It signals society’s distrust and its need to verify claims made upon its pity. It hearkens back to the myth of the Court of Miracles in 17th-century Paris, which we know best from Victor Hugo’s novel, Notre Dame de Paris. It reflects a deeply held cultural attitude about blindness and blind people that goes back much farther than that.

Another haunting aspect of this image is the way in which the photograph was taken. Paul Strand used a bulky 8”X10” large format camera. It was fitted with a trick lens with a right-angle mirror in it. This enabled the photographer to pose as if he were focusing on a fire hydrant or mail box rather than the photograph’s human subject. This was considered to be avant-garde photography in 1916. He managed to take candid shots of people on the street who had no idea that they were being photographed.

To me, that process is a kind of hiding. He certainly did not engage the subjects of his photographs. It reflects the ethical immaturity of Paul Strand as a young man and of photography as a young art form.

The image also haunts me as a piece of visual rhetoric that I want to appropriate for my own purposes.

In my experience as a visually impaired person who has to negotiate access to every conceivable form of printed information, from the gate assignments at the airport to the location of the men’s bathroom to the minutes of yesterday’s committee meeting… in almost every transaction in which sighted people simply read a printed text, I must negotiate access in one way or another. I’ve been doing this day in and day out for 35 years. In that time I’ve witnessed a lot of change in information technology and social attitudes about disability. Nevertheless, the most significant barrier to access for someone who self-discloses that she or he is blind is the stigmatizing gaze portrayed in Paul Strand’s photograph. It is the first and remains the greatest accessibility barrier.

My guess is, in the historical moment in which that photograph was taken, the social engineers who created the system for licensing beggars never imagined that that blind woman had culture or could make culture. She herself may not have believed that she could make culture. Paul Strand probably didn’t give her much credit for that, either.

Curiosity & the Blind Photographer: Introduction | 1. Paul Strand | 2. David Seymour | 3. Henry Butler | Complete talk | Follow the blog thread

Curiosity & the Blind Photographer: Introduction | 1. Paul Strand | 2. David Seymour | 3. Henry Butler | Complete talk | Follow the blog thread

This talk was presented first at MiT5 in April 2007. Then it was titled Re-Imagining Accessibility in Participatory Culture.

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

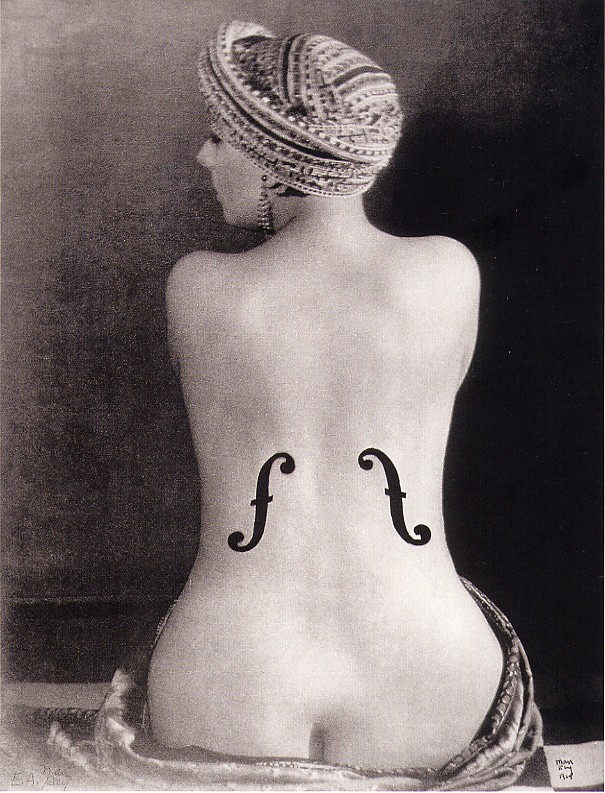

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in  The legendary Kiki of Montparnasse posed for Man Ray’s

The legendary Kiki of Montparnasse posed for Man Ray’s

I too love this picture. So much.