New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer, with his wife, Silda, announces his resignation at his Manhattan office. [Source: NYT]

I admit, I’m as guilty as the next guy when it comes to prurient interest and schadenfreude. I came of age in the reign of Richard Nixon, so I expect sleaze and delusional behavior from politicians, even do-gooders like Eliot Spitzer. Political wives, however, should be spared the grotesque humiliation ritual of standing by their men.

What surprised me about Spitzer’s peccadilloes was how tawdry tawdry has become. As described in Slate, the Emperors’ Club (a “prostitution ring” or “call-girl service”) operated like any other e-commerce site. It even had customer ratings. The “product” description could have come out of the L.L. Bean catalog: “Emmy…. A fine country and folk musician. Her gifted voice and melodious harmony convey nature’s beautiful appreciation at once. She is comforting … rustic. From the warm-toned autumn leaves to the rising flowers of spring, Emmy casually reminds you to savor every second of our surrounding, abundant beauty. Emmy… be revitalized to triumph.”

That’s a $5000 hooker?

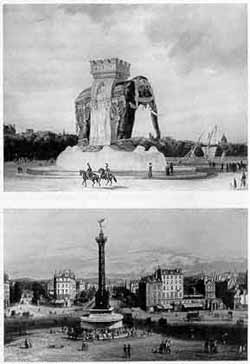

Eliot Spitzer should have consulted Victor Hugo, who knew something about hiding one mistress from another. Consider his elaborate description of the “house with a secret” in Les Misérables (IV.3.1):

About the middle of the last century [i.e., the 18th century], a chief justice in the Parliament of Paris having a mistress and concealing the fact, for at that period the grand seignors displayed their mistresses, and the bourgeois concealed them, had “a little house” built in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, in the deserted Rue Blomet, which is now called Rue Plumet,not far from the spot which was then designated as Combat des Animaux.

This house was composed of a single-storied pavilion; two rooms on the ground floor, two chambers on the first floor, a kitchen down stairs, a boudoir up stairs, an attic under the roof, the whole preceded by a garden with a large gate opening on the street. This garden was about an acre and a half in extent. This was all that could be seen by passers-by; but behind the pavilion there was a narrow courtyard, and at the end of the courtyard a low building consisting of two rooms and a cellar, a sort of preparation destined to conceal a child and nurse in case of need. This building communicated in the rear by a masked door which opened by a secret spring, with a long, narrow, paved winding corridor, open to the sky, hemmed in with two lofty walls, which, hidden with wonderful art, and lost as it were between garden enclosures and cultivated land, all of whose angles and detours it followed, ended in another door, also with a secret lock which opened a quarter of a league away, almost in another quarter, at the solitary extremity of the Rue du Babylone.

Through this the chief justice entered, so that even those who were spying on him and following him would merely have observed that the justice betook himself every day in a mysterious way somewhere, and would never have suspected that to go to the Rue de Babylone was to go to the Rue Blomet. Thanks to clever purchasers of land, the magistrate had been able to make a secret, sewer-like passage on his own property, and consequently, without interference. Later on, he had sold in little parcels, for gardens and market gardens, the lots of ground adjoining the corridor, and the proprietors of these lots on both sides thought they had a party wall before their eyes, and did not even suspect the long, paved ribbon winding between two walls amid their flower-beds and their orchards. Only the birds beheld this curiosity. It is probable that the linnets and tomtits of the last century gossiped a great deal about the chief justice.

The pavilion, built of stone in the taste of Mansard, wainscoted and furnished in the Watteau style, rocaille on the inside, old-fashioned on the outside, walled in with a triple hedge of flowers, had something discreet, coquettish, and solemn about it, as befits a caprice of love and magistracy.

Walk around Faubourg Saint-Germain today, and it’s hard to imagine that such a place ever existed. But stroll all the way to the back of the gardens at the Musée Rodin, duck through the gap in the semi-circular hedge above the reflecting pool, and lo! There could be such a secret passage through the heart of Paris.

A Note on Sources: The text comes from the Project Gutenberg etext of Les Misérables, a sturdy 19th-century translation by Isabel F. Hapgood which is now in the public domain.

When I began quoting and commenting on Les Misérables in September — I’ll call it blog-reading — I didn’t know exactly why I was doing it or where it would lead. I needed content to work with to learn the ropes in WordPress. I was experimenting with text editors in pursuit of “pure text” uncorrupted by hidden Microsoft gremlins. I’d just finished reading Lawrence Lessig’s

When I began quoting and commenting on Les Misérables in September — I’ll call it blog-reading — I didn’t know exactly why I was doing it or where it would lead. I needed content to work with to learn the ropes in WordPress. I was experimenting with text editors in pursuit of “pure text” uncorrupted by hidden Microsoft gremlins. I’d just finished reading Lawrence Lessig’s