Adult double-crested cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus). [Source: Wikimedia Commons]

I was surprised twenty years ago when I began to see double-crested cormorants at Isle Royale. I never saw them on the Great Lakes when I was a kid, when DDT pressure on bird populations was at its worst. In time I saw more and more cormorants from Lake Superior to Lake Erie. A decade ago I witnessed thousands of them gathering at Kelleys Island in the fall migration. Around that time I also began to hear fishermen grumble about “fish thieves.” Soon thereafter came talk of “managing” cormorant populations – that’s what wildlife officials called it. Some fishing guides just went ahead and shot cormorants whenever they saw them in the name of vigilante justice.

This week I’ve been sitting on the Navy Street jetty in Oakville, Ontario. I while away the ours watching the aerobatics of common terns and Caspian terns feeding at the mouth of 16-Mile Creek. I haven’t seen or heard a cormorant yet.

It may be that cormorants pass through Lake Ontario only in the spring and fall migrations. I hope the darker explanations in this story from The Environment Report do not apply here:

Thirty years ago, the double crested cormorant was a poster bird for toxic contaminants like DDT in the Great Lakes. Wildlife biologists used to take live birds with crossed bills and other deformities to public meetings to press for cleanup of the lakes. Since then toxins have been reduced and cormorant numbers have rebounded dramatically. There are now roughly 60,000 of the large black duck-like birds in Michigan alone, but that’s put anglers in an uproar.

For the last decade they’ve been complaining that cormorants are a plague on popular fishing grounds.

Wildlife officials responded by reducing the number of cormorant nests in Michigan by 40% over the last six years, and they want to cut the population in half.

They do that by shooting birds each spring and spraying vegetable oil on their eggs to smother them. In one popular perch fishing area, they took cormorant numbers down by 90%.

Dave Fielder is the lead researcher in the Les Cheneaux Islands of northern Lake Huron for the Department of Natural Resources and Environment. He says he now sees the fishery there doing better and people catching more perch.

“You can’t go in and tweak it a bit and expect to measure. You’ve got to really punctuate the system in a big way so that you’re sure you can measure a response. And that the response can be attributed back to that management action.”

But not all researchers agree with Fielder’s findings.

Jim Diana is a professor of natural resources at the University of Michigan and director of the Sea Grant program in the state. He says many other factors, such as invasive species, contribute to fluctuating perch populations, and Diana says the evidence just isn’t there to show that if the cormorant population is cut in half there will be twice as good a fishery or even any better fishery over time.

“And so it’s all a guess work in my mind. And a guess work at the expense of a fair amount of management money to try to control them and also a cormorant population that many people would say has rights of its own.”

Another place DNRE officials want to hit hard is the Beaver Island chain. They say a large number of cormorants there may be feasting on smallmouth bass.

Nancy Seefelt is a bird specialist at the Central Michigan University field station on the island. When she examines the stomach contents of dead cormorants she finds they are not eating bass. They’re primarily feeding on a small fish called the round goby. The goby is an invasive species that’s exploding in numbers in the Great Lakes. Gobies feed on the eggs of perch and bass. Seefelt says cormorants may actually be helping those game fish populations.

“I think that cormorant control should be based on science and the data that we have as opposed to politics. So the current, I guess, control that’s happening in the Beaver Archipelago is not something I’d say I support.”

DNRE managers argue that cormorant numbers are so high they can’t wait ten years for researchers to come up with more definitive answers, and this summer they expect federal approval to double the yearly kill in Michigan to 20,000 adult birds.

For The Environment Report, I’m Bob Allen.

By the way, the Great Lakes population of cormorants winters in the Gulf states. It’s not yet clear how the oil spill will affect them.

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

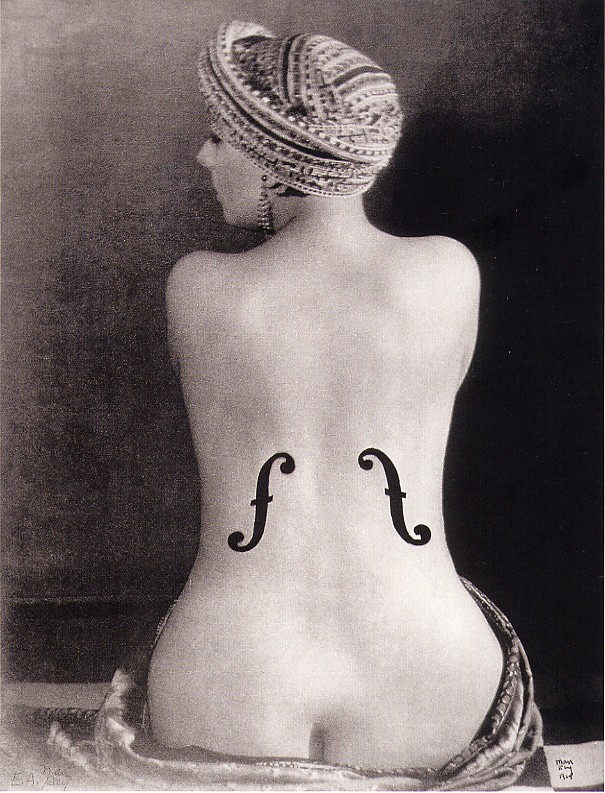

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg) "Brendan, this is what the world looks like all the time to me. Just a little fog. It’s a fine day for boating on the Great Lakes.” Without missing a stroke he turned to dart a skeptical glance at me. Brendan the Navigator. When we named him I didn’t tell his mother everything the legendary Irish name implied. But I imagined him taking on the role of navigator for me. Growing up with Coastal Survey charts and tales of Great Lakes shipwrecks, he came to know Superior as another home. He never doubted the wisdom of canoeing there with a father who was half blind.

"Brendan, this is what the world looks like all the time to me. Just a little fog. It’s a fine day for boating on the Great Lakes.” Without missing a stroke he turned to dart a skeptical glance at me. Brendan the Navigator. When we named him I didn’t tell his mother everything the legendary Irish name implied. But I imagined him taking on the role of navigator for me. Growing up with Coastal Survey charts and tales of Great Lakes shipwrecks, he came to know Superior as another home. He never doubted the wisdom of canoeing there with a father who was half blind. ![ada_signing_072690_ucp_2 President George H.W. Bush signs into law the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) on July 26, 2023 as Justin Dart looks on. [Source: ucp.org]](../wp-content/uploads/2010/07/ada_signing_072690_ucp_2.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

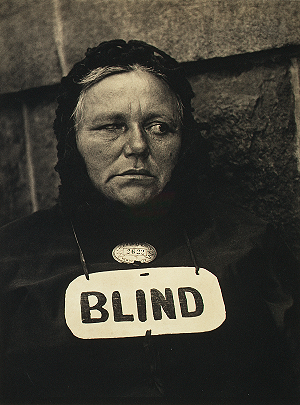

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in  The legendary Kiki of Montparnasse posed for Man Ray’s

The legendary Kiki of Montparnasse posed for Man Ray’s

3 Comments

#1. jonerik 07.09.2023

The same hold true for the white pelican and the loon, which summer in Minnesota and winter in the Gulf. Among other species. We haven’t experienced the end of this yet.

#2. Mark Willis 07.10.2023

Good to hear from you, Jonerik. I hadn’t considered the potential impact of the Gulf oil spill on migrating loons. I believe there are many consequences of this environmental disaster that we do not know now.

#3. Mark Willis 07.10.2023

Update on cormorants on Lake Ontario: they are here in abundance. We saw a flock of about 50 birds flying east in V formation along the lakeshore. A bird photographer working near the Oakville lighthouse told us about a cormorant rookery near Burlington, Ontario. He also showed us a pair of red-necked grebes at the mouth of 16-Mile Creek. I’d seen them before in Alaska but had no idea they were nesting in the Great Lakes region. Their astonishing call sounds like a bleating lamb led to slaughter.

Red-necked Grebe (Podiceps grisegena). [Source: Alaska Loon & Grebe Watch Monitoring Program]

Leave a Comment