The Siren, by John William Waterhouse (circa 1900) [Source: Wikimedia Commons]

I worked on a small literary magazine in the 1970s with a graphic designer who was smitten with the intricate book illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley. I should rummage around in the boxes of geologically stratified ephemera that constitute my literary archive to find a broadsheet with one of my poems bordered by his Beardsley-inspired marginalia.

I haven’t thought twice since then about the 19th-century English artists known as the Pre-Raphaelites, who influenced the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements after them. Beardsley fits in there somewhere, and so does John William Waterhouse, who painted The Siren. Waterhouse was born just a year after the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood formed secretly in 1848 to overthrow academic painting conventions enshrined in London’s Royal Academy of the Arts. Waterhouse was influenced by the work of Dante Gabriel Rosseti and John Everett Millais. By the time The Siren was painted, Waterhouse himself was a pillar of the Royal Academy. By then, the Pre-Raphaelite obsession with erotically charged young women depicted in the throes of untimely death (great-great-great grandmothers of today’s Goth fashionistas) had itself become convention, suffusing the Symbolist movement in art and literature at the turn of the century. The Pre-Raphaelites are said to be the first avant-garde art movement, which sets them up eventually for solid citizenship in the status quo. As Albert Camus observed in L’Homme révolté, “All revolutions are compromised, but human rebellion is constant.”

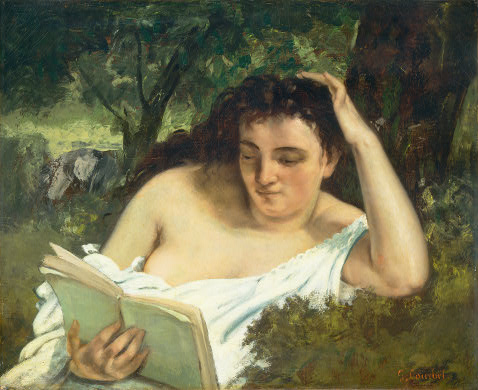

Rosseti, Millais, and kindred spirits like Waterhouse aspired to “the abundant detail, intense colours, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian and Flemish art,” according to the Wikipedia page on the Pre-Raphaelites:

In their attempts to revive the brilliance of colour found in Quattrocento art, [William Holman] Hunt and Millais developed a technique of painting in thin glazes of pigment over a wet white ground. In this way they hoped that their colours would retain jewel-like transparency and clarity. This emphasis of brilliance of colour was in reaction to the excessive use of bitumen by earlier British artists such as [Sir Joshua] Reynolds, David Wilkie and Benjamin Robert Haydon. Bitumen produces unstable areas of muddy darkness, an effect which the Pre-Raphaelies despised.

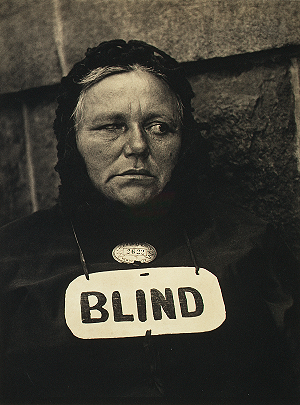

What caught my eye was the gorgeous color in The Siren. It comes through even in a low-resolution, web-based image. I was thrilled with the effect when I inserted the JPEG image here and saw the colors stand out against the subtle background of Moonlight, my WordPress theme. I chose this theme for its soothing compatibility with my peripheral vision. The brightness of a white background on the computer screen wears down my light-damaged retinas, and a black background with text dropping out in white has much the same effect in reverse. Moonlight works just fine for me, on the computer and the terrestrial plane.

Just as salient for me is the flaneur’s path that led me to The Siren. I was reading a Flickr profile for photographer Dave Ward, who maintains that camera quality doesn’t make the great shot. “Credit the photographer’s eye and skill. That’s where the key to good photos lies–in the vision, and the ability to translate that vision to paper or pixels.” I think I agree with that, but I’ll need to complicate its certainty when the photographer and photo editor is a blind flaneur. Anyway, Dave Ward’s profile linked to a Flickr image of an album cover that made use of The Siren. I might have used that image here, but he didn’t offer it under a Creative Commons license. His acknowledgment of John William Waterhouse’s painting didn’t ring any bells until I noticed the first comment below his post. It came from Flickr superstar soleá, who said Waterhouse was her favorite Pre-Raphaelite. That testimonial nudged me to search further, and I found a trove of Waterhouse images in the Wikimedia Commons.

Such are the flaneur’s satisfactions with wayward paths, chance encounters, and unexpected discoveries. Exploring possibilities at the edges of art and eyesight is the raison d’être of the Flaneur’s Gallery.

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in