Dignity, Imagination, and Informed Consent

An essay by Mark Willis (2003)

1. Litany of Defectives

1. Litany of Defectives

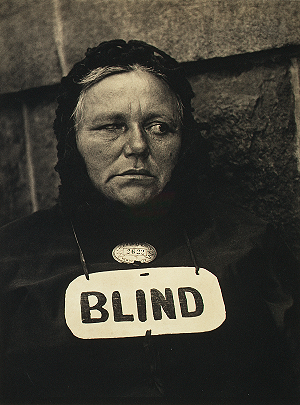

In the heyday of eugenics in the 1920s and 30s, you could not avoid a figure of speech that I will call the “litany of defectives.” You would find it in college biology texts and popular magazine stories about having healthy babies. It was considered by some to be cutting edge science, and you could run smack into it at the State Fair, where stuffed guinea pigs, white ones and black ones, would be arranged on a board to illustrate Mendel’s laws of inheritance. You can imagine which colors represented “pure” and “abnormal” parents and offspring. The display would be accompanied by a version of the litany that went something like this: idiocy, feeble-mindedness, insanity, blindness, deafness, epilepsy, criminality, prostitution, alcoholism, and pauperism are just a few of the undesirable human traits inherited in the same way as color in guinea pigs [1].

A more restrained iteration of the litany was recorded in Buck v. Bell (1927), the landmark Supreme Court decision that upheld the police power of the states to compel sterilization of mentally incompetent people housed in state institutions. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Great Dissenter, spoke for the majority when he affirmed that “heredity plays an important part in the transmission of insanity, imbecility, &c” [2]. Eugenicists in Nazi Germany, who took American legislation as a model when they enacted their own sterilization law in 1933, reduced the litany to one simple, all-encompassing principle: lebenunwertes Leben, or “life not worth living” [3].

These figures of speech engage what bioethicist Bruce Jennings called the “genetic imaginary,” the representation of some hypothetical future life based on a selective focus on genetic information [4]. Prospective parents construct a genetic imaginary of a future child when they make choices about abortion based on prenatal genetic screening. Anyone who tries to understand the meaning of being “at risk” for a genetic disease does so by constructing a genetic imaginary of life with that disease. Even the trendy consumers who are getting their DNA scanned at commercial gene boutiques are engaging in this imaginary process.

I have spent most of my life trying to understand my own relationship with the genetic imaginary. I’ve spent a long time imagining what Holmes’s “&c.” might mean. I admit, I have an overactive historical imagination. In the 1920s I could have been labeled “hereditary defective.” Today we use kinder and gentler euphemisms. I am the carrier - some might say the victim — of two genetic diseases. A third “affliction” may be waiting in my genes. If there is an emerging genetic underclass, as Dorothy Nelkin predicts [5], I could run for class president or class clown.

2. Not This Pig

I first encountered the genetic imaginary in a darkened eye examination room when I was 18 years old. After several years of inconclusive visits to ophthalmologists, I was referred to a retina specialist at the university hospital. Never a good sign. My father took off from work to accompany me through the long day of testing and waiting.

The retina specialist placed a row of 35 mm. slides on a viewing screen in front of me. My eyes were still dazed and dilated from the rapid sequence photography that had produced the slides. I could not have seen much then, but I know now that the images resembled telescopic photographs of the planet Mars, reddish discs replete with canals (the retinal blood vessels) and a polar cap (where the optic nerve enters the back of the eye). The specialist pointed to a yellow cloud at the disk’s center. “See the bull’s eye?” he asked. I did not. But I would know its shape anywhere now - it is the swirl of flashing lights at the center of my vision, the amorphous cloud through which I see the world.

The doctor told me that I had Stargardt disease, a rare form of macular degeneration that had been described first in the medical literature only a few years earlier. Unlike age-related macular degeneration, the most common cause of blindness in older people, Stargardt’s usually began in adolescence or early adulthood. Its progression was unpredictable, and at that time there was no way to treat it.

“You are legally blind now,” the doctor said, “so you probably qualify for some kind of social services.

“It’s hereditary,” the doctor added, “a recessive trait that can skip one generation and show up unexpectedly in the next.” He looked to my father and asked, “Is there any other history of eye disease in the family?”

My father paused and took a deep breath. Something troubling in his experience as a parent, something he could not solve for his children, began to come clear in his mind. “Mark’s older sister has had eye problems ever since she was a little girl. We took her to one doctor after another, and no one could tell us what was wrong.” That is how my sister Diana, then age 30, came to be diagnosed with the same genetic disease.

Before the specialist left the room, he said, “There may not be a cure now, but there is always the hope that research will find one someday. If there is a research study, would you be willing to be in it?”

“Maybe,” was all I said then.

“We don’t see this very often,” he added. “Do you mind if the residents take a look?” I wanted to withdraw somewhere deep inside myself, to figure out what all this meant, but I agreed. That was my first experience with informed consent.

Seven or eight young doctors in training lined up to shine ophthalmoscopes into my eyes. I began to sink after the third resident took a long, probing look. I felt like I might pass out. My father recognized my distress and stepped between me and the next doctor. “That’s enough,” he said. “You’ll have to learn about it some other way.”

My father became the guardian of my dignity then. Years later, our roles would reverse, and his quiet, decisive way of stepping in would be a powerful model for me.

Several days after my diagnosis, when I thought more about the prospect of becoming a guinea pig in a research project, an answer came clear in my mind. “Not this pig.” This was my first oral formula, a mnemonic device like Homer’s “wine-dark sea,” a cluster of words that can summon from memory a complex array of feelings and experiences. It became my way of claiming and reclaiming the terms of an evolving relationship with the genetic imaginary.

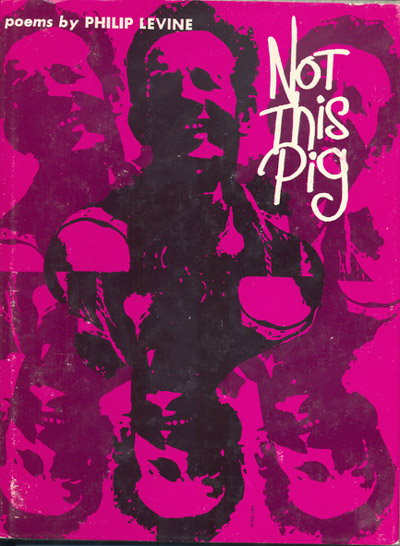

Not This Pig was the title of a book of poems by Philip Levine, and the last line of a defiant poem called “Animals Are Passing From Our Lives” [6]. The poet speaks in the voice of a pig being driven to market. It can smell the butcher’s block and blade. It can imagine “the pudgy white fingers/that shake out the intestines/like a hankie,” but it won’t fall down or squeal. Levine said the poem celebrated “digging in your heels” [7]. That pig held on to its own stubborn sense of dignity, and so would I.

3. Life Not Worth Living

The next encounter with the genetic imaginary occurred 20 years later. I was 39. I was having a heart attack. As my heartbeat slipped away in the emergency room, I lost consciousness. I felt as if I’d fallen to the bottom of a well. I didn’t see the apocryphal light that others have reported at the edge of death, but I heard a voice. It was my voice. It was saying, “Mark, what the hell are you doing down here?”

After a jolt of atropine, my heart started again and my eyes opened. I heard the emergency physician say, “Mark, come back.”

Then a nurse ran my gurney down the hall to the cardiac catheter lab. Another nurse jogged along side me. She held up a clipboard and explained, “This is a consent form.”

“I can’t see that,” I said.

“That’s OK.” There was something gentle in her voice that I needed to hear then. “It says that you understand and agree to have a heart catheter procedure. Depending on what happens with that, you may go right into surgery. This form also gives your consent for open heart surgery if it’s needed.”

I don’t know how many seconds it took for that to sink in. As I scrawled my signature, illegible in the best of circumstances, I knew that this might be the last decision I would ever make. In that moment, all my dignity as a human being was focused in the simple act of making that decision. Now, and from this distance, you might say that the act of signing a consent form then was purely a formality, something the hospital’s lawyers required in the name of risk management. Had I lost consciousness again, they would do whatever they had to do anyway, whether I signed or not. But I saw it differently. I was being given a choice, and I was determined to choose for myself.

I flirted with tachycardia in the catheter lab. I heard a remote voice on a speaker shout, “De-fib!” The imaging cameras swung out of the way. A nurse came toward me with defibrillator paddles. In an instant I thought, “Settle down, boy, you’re about to get electrocuted.”

My heart settled down. Another voice said, “Wait.” The nurse was close enough for me to see her face and make eye contact, an intimacy I experience but rarely with strangers. I watched emotions race across her face: fear, mercy, resolve to act, relief at not having to do so.

After another hour of clot-busting drugs and angioplasty, my coronary arteries were open again. I was transferred to cardiac intensive care. I felt a fleeting sense of euphoria when I found my children waiting for me there.

Eventually I realized that I had been in this hospital room before. My father had been placed in the same room after suffering ventricular tachycardia and irreversible brain damage following a heart attack. It was there, listening to the rhythmic pulse of the respirator that sustained his breathing, that I began to imagine what “persistent vegetative state” means. He lived in a coma for eleven months. I became the guardian of his dignity then. Once I had to ask a hospital social worker to step out of this room when she tried to discuss end-of-life decisions as if he were not there.

Our family history of heart disease was not new to me. Several years after my father’s death, I was diagnosed with a familial type of lipid disorder, which a premature heart attack now confirmed. This was my second genetic disease. I didn’t just give a family history to every doctor who asked - I was re-living it. Later that night, as my heart lurched through its own arrhythmias, I heard one nurse say to another, “Keep an eye on this one.”

The informed consent dialogue continued at intervals over the next two days as my cardiologist discussed the options. He believed the angioplasty was only a temporary fix and recommended coronary bypass surgery. I agreed but needed time for my sister to travel here. She was the next of kin who would serve as my guardian and proxy decision-maker.

I was talking with Diana when I lost consciousness again. When I opened my eyes sometime later, I heard her wailing in the hall. The cardiologist and a team of nurses were working on me. “Your arteries are closing up,” he explained. “We’re getting you ready for surgery now.”

Diana was present when the heart surgeon came in to talk with me. By that time I was as scared as I’ve ever been. He offered me a mild sedative. This man projected a calm, reassuring bedside manner as he explained what was about to happen.

Then he added, “There is a slight chance, maybe one chance in a hundred, that you will throw a blood clot during the surgery. This means you could have a stroke. Worst case scenario? massive brain damage. We could do all the heroics with life support, but maybe the best thing would be to just let you go.”

The sedative was beginning to take effect, and I struggled to stay awake. Was he really saying that? I understood that I might end up trapped in a life not worth living. Lebenunwertes Leben? Many people say they would make that rational choice rather than prolong life in a persistent vegetative state. That’s supposed to be the choice with dignity. But at that moment, vegetable or not, I wouldn’t say yes to death.

“I want a chance,” I said. “”I want to live.” Then I fell asleep, trusting that my sister understood what I meant.

4. Informed Dissent

Several years ago, the phone rang at home after dinner one night. My son Brendan answered it, ever wary of the telemarketers who swarm like mosquitoes as the sun goes down and people begin to relax. Brendan was 14 then, and he had my permission to goof on telemarketers however he wanted. Something in the voice on the other end made him restrain himself.

When I picked up the phone, Dr. X said, “Mr. Willis, I’m waiting for you to return the signed consent form.” Dr. X was a young physician-scientist at a prestigious research university who was searching for the gene that caused my eye disease. We had talked on the phone once before, when I was in my office at another university. He wanted me and my family to join his research study. I was the point of entry for an entire “pedigree,” as geneticists say.

“I haven’t had a chance to read it yet,” I said a little sheepishly. My life is filled with stacks of unread papers, preserved through time and neglect like the geologic record. I trust the stratification, and maybe someone will come along who will read some of it to me. I felt that I could be honest with Dr. X. After all, he was devoting his career to curing my disease.

“It’s a long, technical document,” I continued, a touch of defensiveness in my voice. “The type is smaller than what I can manage these days.”

“You could just sign it. All we want is a blood sample.”

“No,” I said. “I need to read it. The part about ‘informed’ is just as important as the part about ‘consent.'”

“When will you be able to read it? We don’t have a lot of time.” He sounded impatient and a little angry now. He repeated his recruitment pitch. “We’re close to identifying the gene for your problem. You know how important this research is. In a year we’ll have a screening test. Then you can find out if your son will get Stargardt’s. The screening will be free, of course, for participants in the study.”

I was getting angry now, too. I wasn’t ready to bring Brendan into this or debate the social risks of genetic screening. “Look,” I said shortly, “I need to read your document before I consent. I need to read all of it. Can you send me a tape or read it to me over the phone?”

“Can’t your wife read it to you?”

“My wife?” I could hear stigma piling on top of stigma like a litany: blind, genetic defect, single parent? was this an audition for the Jukes family? Getting a grip, I said, “I don’t have a wife. Even if I did, that’s not the answer. If you’re going to do research with blind people, you have an obligation to provide them with reasonable accommodations.”

“We don’t have money for that,” Dr. X said.

“Well, then, not this pig.”

I wanted to say that, but something in this busy scientist’s voice made me hold back. He didn’t even know that we were negotiating.

“Good night, doctor,” I said. “I’ll read it when I can.” I never did, and my family has not yet donated its genotype to science.

5. Improvising on the Genome

In the name of full disclosure, I should make it clear that I am not a 21st-century Luddite who categorically opposes the advance of science. After all, I make my living as a science writer at a medical school. I am a disability rights activist, but I cannot muster an “undifferentiated moral condemnation” of the medical model [8], as it is represented sometimes in the discourse of disability studies. I was interested in joining Dr. X’s study out of intellectual curiosity. I’ve volunteered for several human research projects, and none of them posed a risk to my well-being or dignity. I have imagined the circumstances in which I’d take experimental risks in the management of my heart disease, and I know I could make the decision without much time to think about it.

Hoping for an experimental cure for my eye disease, however, is not even a blip on my sonar screen. A geneticist who has heard my stories asked me once about this difference in attitudes. The simplest answer is this: unlike heart disease in both its acute and chronic dimensions, I do not experience vision loss as a disease. It is a different way of perceiving the world, and it is rich with its own sensory skills and sweet satisfactions. I think of myself as socially blind; the deficits associated with my blindness result more from society’s limitations than from a disease process active in my body.

Instead of looking to DNA for answers, I’ve lived my life by improvising on the genome. This is the story that reaches beyond the script encoded in my genes. It’s the story I make up as I go. It’s a body of knowledge and experience with making adaptations and negotiating accommodations. I am not likely to enter someone else’s construction of the genetic imaginary unless it makes room for this body of lived experience.

In my case, it is a family story, too. My sister has been a guide and mentor throughout my life. Today she is a master teacher with a special education classroom devoted to early childhood intervention, and she brings to it a disability activist’s commitment and a grandmother’s wisdom. Together we have more than a hundred years of experience with our disability, and we put our faith in that.

About a month after Dr. X called, Brendan was reading to me from an essay in Mikhail Bakhtin’s The Dialogic Imagination. The abstruse prose studded with Russian linguistic terms was rough sledding, but he agreed to try it after the audio tape broke. By the age of ten, Brendan could read anything, and he often read aloud to me. I thought in passing that he could have read Dr. X’s consent form to me, until I remembered that it involved his genes as much as mine.

Something in Bakhtin’s radical social ideas about language resonated with Brendan. He stopped reading and confided to me that when he grew up, he wanted to be a rebel rather than middle class.

“Me, too,” I said. “On the surface, I have all the trappings of a middle-class life - credit cards, a house, a college education. But I don’t think anyone’s vision of the middle class includes living with a disability.”

Then my son revealed a glimpse of his own construction of the genetic imaginary. “You know, dad, I used to think it was sad that you were going blind. Now I think it is just the way you are. I can’t imagine you any other way.”

6. A Still Small Voice

When I was a child, and there was no limit to my reading, a biography of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes captured my imagination. Yankee from Olympus [9] cast the Great Dissenter in a heroic mold, and it led me to his eloquent dissenting opinions on freedom of thought and expression. By the 1960s, these minority opinions had prevailed as precedents of First Amendment law. Justice Holmes argued in the 1919 case of Abrams v. United States that government must not ban or punish seditious speech for fear of its consequences. “The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas,” he wrote; “the best test of truth is the power of thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market” [10]. I put this in my own words and took it as a credo: speech, no matter how extreme, must be trusted to the free marketplace of ideas.

Yankee from Olympus did not mention Buck v. Bell. I could never have imagined as a child that one day I would hear the decision’s most notorious argument — “Three generations of imbeciles are enough” [11] — and feel betrayed.

Justice Holmes never met Carrie Buck, the plaintiff in this case. He accepted her diagnosis as an imbecile, and consigned her to the litany of defectives, on the authority of written testimony from experts. He had to imagine what a life of imbecility might mean, and he imagined life not worth living. “It is better for all the world,” he wrote, “if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind” [12].

That was Justice Holmes’s construction of the genetic imaginary. The U.S. Supreme Court codified it as the law of the land and stamped it with the highest authority to enforce decisions that led to the sterilization of thousands of Americans.

The judicial weight of Buck v. Bell underscores the first point I want to make. At the intersection of law, medicine, and science, institutions wield great power to shape both the information and the decisions we make in the informed consent process. According to Bruce Jennings, “We must not underestimate the power of science and technology to colonize and dominate the contemporary imagination” [13]. In other words, when we make decisions based on informed consent, especially in circumstances when our autonomy is most vulnerable, the marketplace of ideas may not be as free as it should be.

My final point emphasizes the experience of families in this process. When Dr. X asked me to join his genetic study, I had legal responsibility for me, for my son who was a minor, and for my mother. She had Alzheimer disease (that is the third affliction that may be waiting in my genes) and I was her guardian and medical decision-maker while she lived in a nursing home. Like Justice Holmes, I could have rendered a pragmatic, paternalistic decision for three generations. I was prepared to give my DNA sample to Dr. X, but I knew I would wait for my son to make his own decision about it, no matter how long that might take. I needed to read the informed consent document carefully to know how it would protect his privacy and mine.

By the time Dr. X called me at home, I also knew that I could not make this decision for my mother. It was just a blood sample, as the doctor said, and she might have forgotten all about it five minutes after the needle stick. Or her memory might have stuttered about it in ways I could not know. When she was competent to make her own decisions, she would have signed a consent form had I asked her, but she never would have done it without my influence.

I could say I was the guardian of her dignity then, but really, family roles reversed one more time. At the end of her life, my mother was demented and paralyzed and nourished with a gastric feeding tube. Her final stroke took her swallow function and ability to speak. Some people would say that is a life not worth living. In her presence, though, I was reminded of Emerson’s simplest statement of faith: “I believe in the still small voice” [14]. Her serenity and acceptance of her body gave me one more lesson in the awesome dignity of living life out however it unfolds. With one moveable hand, my mother remembered how to take a flower and raise it to her nose to sniff. This is how we conversed.

We were improvising on the genome. Life’s improvisation remains an unfinished project for all of us. I believe each of us can play a part in it no matter how small the voice. For that, three generations are not enough.

Notes

[1] See Daniel J. Kevles, In The Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (New York: Knopf, 1985), ch. 4.

[2] 274 U.S. 206 (1927).

[3] See Robert Jay Lifton, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (New York: Basic Books, 1986), p. 20. Lifton translates lebenunwertes Leben as “life unworthy of life.”

[4] Bruce Jennings, “Technology and the Genetic Imaginary: Prenatal Testing and the Construction of Disability” in Erik Parens and Adrienne Asch (Eds.), Prenatal Testing and Disability Rights (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2000).

[5] Dorothy Nelkin, “The Social Power of Genetic Information” in Daniel J. Kevles and Leroy Hood (Eds.), The Code of Codes: Scientific and Social Issues in the Human Genome Project (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 190).

6. Philip Levine, Not This Pig (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1968).

7. Quoted in Remnick, David. “Interview with Philip Levine,” Michigan Quarterly Review 19 (1980): 382-98.

8. See Lifton, p. 503, on his struggle with bearing witness without losing critical focus through “undifferentiated moral condemnation” of medical killing in the Holocaust.

9. Catherine Drinker Bowen, Yankee from Olympus: Justice Holmes and His Family (Boston: Little Brown, 1944).

10. 250 U.S. 630 (1919).

11. 274 U.S. 207 (1927).

12. Ibid.

13. Jennings, p. 141.

14. Quoted in Robert D, Richardson, Jr., Emerson: The Mind on Fire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), p. 158. The Biblical source for the phrase is the story of Elijah and the still small voice (1 Kings 19). Richardson places Emerson’s statement in the context of his affinity with Quakerism in the 1830s.

Acknowledgments

This essay is reproduced here with permission of Gallaudet University Press, which published it in 2004 in Genetics, Disability, and Deafness. An early draft was presented as an oral performance at Gallaudet University’s conference of the same name in March 2003.

Thanks also to Philip Levine for permission to use the title of his extraordinary book of poems, Not This Pig.

The Ohio Arts Council awarded the author an Individual Artist Fellowship for this essay in 2004.

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

Pingback: a blind flaneur

Pingback: a blind flaneur

Pingback: April 19: Clinging to Life at the Nexus of Private & Public Terror - a blind flaneur

Pingback: Mapping Controversies in Citizen Bioscience - a blind flaneur

Pingback: Mapping Controversies in Citizen Bioscience - Fair Use Lab

Pingback: Philip Levine Is Named U.S. Poet Laureate | a blind flaneur