Notes on the Ecology of Negotiating Accommodations

A Talk by Mark Willis

1. Interface

I call this talk “Notes on the Ecology of Negotiating Accommodations.” I need to make a disclaimer right at the outset. I do not do PowerPoint’s, and I will not show you slides with quadratic equations or sophisticated computer modeling. My command of the science may be outdated. When I say ecology, I really mean what I call ecology myth in one of my other writing projects. Ecology myth is a set of ideas and values acquired when I was a child in the 1960s. These ideas and values have continued to shape my understanding of systems and processes, complexity and diversity, throughout my life as a person with a disability.

So one goal of this talk is to look at the experience of disability in ecological or eco-mythical terms. I’ll examine my own experience with negotiating reasonable accommodations that I used to get from point A to point B in a busy airport. And I’ll call on three ecological concepts: interface, ecosystem, and energy budget.

Another goal of the talk is simply to tell you a story about accommodation. I know some sessions at this conference have discussed accommodation from the technical (that is, the legal or policy) perspective. Others have explored the process from technological perspectives. I could call my approach existential or epistemological. I want to convey something of what it feels like to negotiate accommodations on a daily, even an hourly, basis. I know I will not fill the time allotted to me - always a good strategy for the session preceding lunch - so I hope my story will induce you to share some of your own stories about accommodation during our discussion time.

As I said, I do not do PowerPoint’s, but you can close your eyes and think of my opening story as the Dilbert cartoon that often graces this kind of presentation. This story happened to my friend and mentor Scott Marshall, a Washington attorney who works now for the Federal Communications Commission. In the 1980s and 90s he was government relations director for the American Foundation for the Blind. Shortly after the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed, Scott was invited to talk about it to a convention of police chiefs. If this conjures up memories of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, you’re on the right track. Scott talked, and the police chiefs listened politely. When it was time for the Q and A, what do you suppose police chiefs wanted to know most about the ADA?

Scott expected some kind of question about the police role in settling on the spot disputes about disability discrimination. He thinks like a lawyer, not a police chief. This is what they most wanted to know: What part of a wheelchair can be used as a weapon?

Scott’s story illustrates my first ecological concept: the interface. In ecology, an interface is a zone of contact where two distinctly different habitats share a border. Less adaptive species in one habitat avoid alien conditions in the other. More adaptive species flourish in the mix. It presents harsh limits to some, and greater diversity of opportunity to others. Scott’s experience at the police chief convention represents an interface where two vastly different perspectives on disability could make contact and mix it up.

Every time a disabled person negotiates an accommodation with a nondisabled person, no matter how simple or routine the accommodation, there is an interface where divergent attitudes about disability can collide. I believe such interfaces are also rich with existential possibility. Let me tell you another story.

2. Ecosystem

![Saddam’s statue is pulled down by U.S. Marines using a wench on a tank.[Source: AP/Guardian] Saddam’s statue is pulled down by U.S. Marines using a wench on a tank.[Source: AP/Guardian]](../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/saddam_statue_topples_041003_2.jpg) It happened in April 2003 when I was traveling from New Orleans to Dayton via Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport. The day began with carefree dancing in the street at the French Quarter Festival, and it almost ended on the tarmac in Atlanta in the middle of a terror alert.

It happened in April 2003 when I was traveling from New Orleans to Dayton via Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport. The day began with carefree dancing in the street at the French Quarter Festival, and it almost ended on the tarmac in Atlanta in the middle of a terror alert.

When I look back now I realize there were portents of this trajectory. As I reluctantly packed my bags at the hotel on Royal Street, the television was tuned to CNN. I don’t own a television, and I seldom watch TV unless I’m stuck somewhere in a hotel. April 2003 was the peak of “major combat operations” in the ongoing Iraq war. The top news story that day - the story repeated over and over again as I passed from airport to airport on my journey home - was the toppling of the Saddam Hussein statue in Baghdad.

As my first flight neared Atlanta, a Delta flight attendant asked me what kind of assistance I would need at the airport. He had a passenger list in his hand indicating that I had requested assistance when I booked the flight months earlier. The first step in negotiating accommodations was getting the request in the airline’s reservation system. I was reassured, if only for a few minutes, that everything was set in Atlanta. I told the flight attendant, “I need someone to tell me or show me how to get to the gate for my connecting flight. That’s all. ”

“No problem,” he said. Someone would be waiting at the arrival gate to assist me.

When I arrived at Gate 5, Terminal A, it was 6:55 p.m. I heard Saddam’s statue topple on a TV monitor in the waiting lounge. As often happens in airports, no one at Gate 5 had any idea that I needed an accommodation. The Delta gate agent told me that my connecting flight would leave from Gate 39, Terminal E, Atlanta’s international terminal, in a little less than an hour. Why a flight to Dayton was departing from the international terminal was just one of those last-minute exigencies of airline scheduling.

Most people get from terminal to terminal in Atlanta using the airport’s subway. I had done that before. It reminded me of the Metro in Washington, D.C. I told the gate agent I could take the subway to Terminal E if she could give me precise directions about where to turn to get on the right escalator.

She looked dubiously at my white cane and said, “No, no. We can get you there on a shuttle bus. I’ll call for someone to take you to the shuttle.”

This was the second step in the negotiation, and I had just given in.

I should explain here that I have been an ad hoc cane user for years. I use the cane as an orientation and mobility too only when I need it, depending on the situation. This usually means when walking at night and traveling in unfamiliar or unpredictable environments. Some airports are familiar to me, some are not. All airports are unpredictable places, so I’m sure to use the cane to navigate through them.

Over the years I have strenuously resisted the suggestion that I should always use a white cane, if only to alert others about my visual disability. It’s a mobility tool, I reply, not a symbol, not a stigma.

It was 7:05 when an airport worker arrived with a wheelchair to take me to the shuttle bus. I politely declined the wheelchair. Then, to my amazement, he took the tapping end of my cane and proceeded to walk away, expecting me to follow him. He didn’t know it was a folding cane. I stood my ground. When he reached the furthest stretch of the elastic cord inside the cane, he turned around to see what was wrong.

“Let go,” I said. “”The cane is my tool, not yours.”

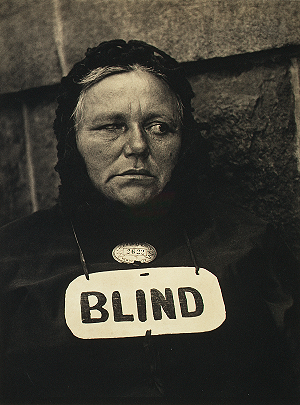

I remembered a photo that I saw years ago in Natural History magazine. In it, a child towed an old blind woman with a stick. Each of them grasped an end of the stick, which was about five feet long. They lived in a remote village in Guatemala where onchocerkiasis, a parasitic disease also known as river blindness, was endemic. A stick picked up off the ground seemed like a simple, readily achievable accommodation in that context, but it also served to maintain a safe, prophylactic distance between the guide and the guided.

This brings me to the second concept that I take from ecology. Ecosystem. An airport is a complex ecosystem. It is a physical environment, of course, and it supports multiple, interdependent processes that are happening simultaneously. It is comprised of many different constituents who fill niches up and down the food chain. My guide was an employee of the Atlanta airport, not Delta Airlines. My accommodation was no longer the airline’s responsibility. Whatever I thought I had negotiated with Delta was back on the table and up for grabs. This airport worker represented a new interface.

So I explained to him, “I can see enough to follow you. Just head for the shuttle.”

He accepted this grudgingly. He led me across the concourse to a door marked “Authorized Personnel Only.” We entered a hidden airport domain which most passengers never see. We walked through empty corridors, descended an elevator, and arrived at a ground-level waiting lounge. It was only 7:15, but I felt the first apprehension that I would never make the connecting flight to Dayton.

As I waited, I checked my watch nervously and thought, “If I’d taken the subway like everyone else, I’d be at Terminal E by now.” I could listen to the bus’s wayward progress across the airport on a two-way radio used by the driver and a dispatcher. It sounded like chaos out there. And of course, I heard Saddam’s statue topple again on an overhead TV monitor.

The shuttle reached Terminal A at 7:25. My initial guide was long gone. Escorting me to the bus was the responsibility of yet another airport worker - one more interface. The negotiation began all over again. I assured her I did not need a wheelchair, and to her credit, she did not grab my cane.

The bus ride proved as nerve-jangling as I expected. Jet planes had the right of way, and we lurched and halted fitfully every time a jet crossed our path. There was one fellow traveler on the bus, a seven-year-old bombshell named Keisha. She was traveling unaccompanied from her dad in one city to her mom in another. Out there on the tarmac, the bus driver acted in loco parentis for Keisha. In a way, Keisha acted in loco parentis for me. Every time a jumbo jet loomed large in my peripheral vision, I flinched. Keisha hooted with glee. She wanted to ride the bus’s brake and gas pedal. She was an old pro when it came to crossing the Atlanta airport. In her company I stopped worrying about the time. When Keisha got off the bus at Terminal D, I felt abandoned. I told the driver, “That girl’s going to own Delta Airlines someday.”

Finally, Terminal E. Another waiting lounge; another TV monitor - you know what was on CNN. It was 7:45 p.m. Fifteen minutes to catch my plane. Another escort; another interface. She took me up an elevator. As soon as we stepped into another empty corridor, a loud bell started ringing. It sounded like a fire alarm. My escort ran to a security door and frantically punched numbers on a small keypad. Nothing happened. She ran back to the elevator. The doors had closed and wouldn’t open again.

“Oh, no,” she said. “It’s a lock down!”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“An international flight is coming in. The terminal gets locked down. No one gets in or out until a security team sweeps the plane.”

Evidently this was a standard procedure now for Alert Level Orange or Red or whatever it was. I started worrying again. It was 7:49. From this point on, things happened so fast I can’t quite believe what I’m about to tell you.

My escort panicked. She grabbed my arm - no time for negotiating niceties now - and we ran down the corridor and turned onto a jet way. Halfway down the jet way, she opened an emergency door in its accordion side-wall and stepped out onto a narrow metal fire escape. I followed her out and was almost knocked down by the roar of jet engines.

The fire escape teetered under our weight. She ran down the steps two at a time. I froze at the top, trying to get my bearings in the middle of all that noise. Hearing wouldn’t help me now. What was going on? Did Saddam feel this kind of vertiginous careening out of control right before he toppled?

Then I felt the reassuring hand grip of my cane. My cane! I’d been clutching it all along. Now it would work like the simple tool it was designed to be. Not a symbol, not a stigma, not an invitation to the clumsy good deeds of others. I took a deep breath and tapped my way methodically down the steps.

When I reached the tarmac I was calm enough to stop and take in the scene. A Boeing 747 is an awesome thing when you are standing beneath it. No one else was out here, boots on the ground. Presumably, if a terrorist escaped from this incoming flight, he would be isolated on the tarmac, just like me. Maybe there was a SWAT team on the roof of Terminal E. Maybe someone was studying me through the interface of a sniper scope. I hoped he wasn’t wondering, “What part of a white cane can be used as a weapon.”

My escort was standing in the waiting lounge doorway. She was flailing her arms to get my attention. She was shouting, but I couldn’t hear anything. We quickly retraced our route - elevator, empty corridor, security door. This time it opened and I stepped dazedly onto Terminal E’s mostly deserted concourse. It was 7:57. I had three minutes to get to Gate 39.

I was handed off to yet another airport worker. When he took my arm I pulled back, in no mood to negotiate now. I realized that I wasn’t calm, after all. I was in shock. My heart was pounding and I was ready to fly into an adrenalin-suffused rage. Then I got a grip - the cane’s hand grip again. I swung the cane emphatically to clear a path ahead of me and started walking.

My new guide’s co-workers witnessed this scene and interpreted it as homophobia. They teased him about it loudly, which only added to his embarrassment. He shuffled sullenly toward Gate 39. I wanted to run.

It was 8:02 when we got there. A ticket agent waived me through the jet way entrance saying, “Hurry! They’re holding the door!”

When I stepped onto the plane, the flight attendant was waiting with a passenger list in hand. She said, “Mr. Willis, where have you been?”

3. Energy Budget

The final ecological note I want to discuss is the concept of energy budgets. Every organism in an ecosystem has an energy budget. Think of it as a balance sheet or profit/loss statement where the currency is counted in calories of heat. An organism expends X calories of energy to acquire Y calories of nourishment. If X>Y — and that’s as complicated as my ecological equations will get - that organism will not flourish.

Here’s a more concrete example of what I’m talking about. It comes from one of my most beloved ecosystems, Isle Royale National Park. Isle Royale is a remote wilderness island in Lake Superior. Wolves are the top of the food chain there. Moose are what they hope to eat in winter. With its long legs, a moose can outrun a wolf pack in deep snow. It runs clumsily on the ice of frozen lakes, however, and becomes more vulnerable prey. Even though it’s the top of the food chain and there might be plenty of moose around, a wolf’s energy budget can be depleted if it has to hunt in deep snow. Then it starves.

I felt like a bottom-feeder by the time I fastened my seat belt on that flight to Dayton. In the teeming ecosystem of Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport, I had just passed through half a dozen human interfaces in an hour to get from one airplane to another. Sometimes I held my ground, sometimes I went with the flow, sometimes it didn’t matter what strategy I tried because events had an unexpected momentum all of their own. My energy budget for negotiating accommodations was spent.

One parsimonious bag of airline pretzels later, however, my spirits began to rise. When I thought of Keisha, her traveler’s excitement and aplomb, I had to smile. When I thought of Saddam’s statue, so phony on so many levels, I had to laugh. Maybe friction at the interface is an inevitable cost in the energy budget of living with a disability. I began to see what I had just experienced as one more problem to be solved. The next time I passed through the Atlanta airport, I’d make a mental map of the subway system. I would reduce the coefficient of friction. I would find my own way.

* * *

Acknowledgements: My thanks go to Scott Lissner and the staff of the ADA Coordinator’s Office at The Ohio State University for the opportunity to present this talk at the 2005 conference on Multiple Perspectives on Access, Inclusion, and Disability. A tip of the hat to Hartsfield International Airport and Keisha, wherever she may be, for giving me so much food for thought.

About the image: Saddam’s statue was pulled down by U.S. Marines using a wench on a tank. It was big news in Baghdad on April 9, 2003. An Army report concluded later that the statue’s demise was not a spontaneous expression of Iraqi freedom. A Marine colonel first decided to topple the statue, and an Army psychological operations unit turned the event into a propaganda moment. [Source: AP/Guardian]

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

Pingback: a blind flaneur