A talk by Mark Willis (2004)

[This talk was presented at a genetic counseling seminar at the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, on April 2, 2004. My thanks go to Aideen McInerney-Leo and Barbara Biesecker for the opportunity to share my perspective on disability and genetic disease at NIH.]

1.

I want to begin by reading you the very bad first line of a novel that will never be written. It’s a winner in the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest. Edward George Bulwer-Lytton was the Victorian novelist who gave us the infamous opening line, “It was a dark and stormy night.” Every year in his memory, wretched writers are asked to imagine the worst and go no further. So the winner is:

The sun oozed over the horizon, shoved aside darkness, crept along the greensward, and, with sickly fingers, pushed through the castle window, revealing the pillaged princess, hand at throat, crown asunder, gaping in frenzied horror at the sated, sodden amphibian lying beside her, disbelieving the magnitude of the frog’s deception, screaming madly, ‘You lied!

I don’t do PowerPoint presentations, for a variety of reasons. But you can think of this as my equivalent to the opening PowerPoint slide with the Dilbert cartoon on it. Actually, a friend in Toronto dared me to use this line in one of my talks. When I heard it, I thought, “Yes. I can make it work.” It works on different levels for different audiences. If I were talking to the Modern Language Association (the MLA), I’d probably get into the postcolonial exploitation of amphibians as sexual signifiers. Here at NIH, I could allude to the dangers of transgenic experimentation in our post-human future.

It’s a campy, Mae West-kind of line, so bad it has to be good. That’s because it plays off the archetypal stories we learned as children, the fairy tales and folk tales. Animals in those stories became characters with personalities. They also became symbols for ambiguous things not explicitly said in the stories. There are deeper psychological processes going on here, which the environmental journalist Peter Steinhart explained this way: “We don’t only think about animals: we think through them. They become mental forms around which we wrap ideas, hopes, fears, and longings.”

So I want to tell you a personal story about animals that also thinks through them. It’s become fashionable to call this sort of thing a thought experiment. In a sense, it’s not so different from the experiments taking place right now, in this building, with any number of nematodes, zebra fish, and knockout mice. We think through animals.

I could tell you stories about frogs. When I was a kid I was a budding junior naturalist, and for a couple of years I wanted to devote my life to the science of herpetology. Somewhere along the way I became a writer instead. Instead of frogs, I will aim a little higher on the food chain and talk about one of the charismatic mega-fauna, the kind of animal portrayed on the cover of glossy environmental magazines.

2.

My story takes place in September, when the salmon are running, on a deserted stretch of wild beach on the south shore of Lake Superior:

I saw them first encircling a tree trunk half buried in the sand. Only a foot or two from that morning’s wave line, wet with spray, the log looked like the carcass of a beached seal. This was the edge of a freshwater sea, Lake Superior, so seals were not a possibility. The tracks encircling this log seemed almost as unlikely. Once upon a time I would have doubted their possibilities as much as the presence of seals.

I followed the tracks up the sand to the forest’s edge, where they disappeared in the leaf litter and moss. Then I backtracked to the log. Whatever made the tracks had trotted easily up the beach into the woods, but only after it circled the log slowly, deliberately. The tracks sank deeper into the wet sand there. It must have sniffed as it circled. Then it probably paused and lifted a leg.

I looked east, toward camp, then west toward the mouth of Pendills Creek. I scanned the beach with binoculars. As far as I could tell, there was no one else on the beach for miles in either direction. So no one would see me when I dropped on one knee, leaned hard on my oak walking stick, and put my face so close to the log I could kiss it.

All I could smell was the punk of a water-logged pine. The log’s scents had more stories to tell, but the acuity of my nose, like that of my eyes, was too limited to discern them.

I resisted the moment to moment identification that was forming in my mind. These were large tracks, almost as long and broad as my hand. They were canid tracks. Beyond that, I couldn’t say with much certainty. In every other year that I had walked the beach along Whitefish Bay, I would have said these were the tracks of a very large dog. But now I wondered.

The log appeared to be a terminus, a marker, the eastern-most point of the animal’s journey. I headed west again. It’s eastbound trail was indistinct along the water’s edge.

After wading across the mouth of Little Creek where it makes its modest contribution to the oceanic immensity that is Lake Superior, I saw another set of tracks. Human footprints, also eastbound, skirting the water line. Their gait was a plodding trudge. The tracks were punctuated with a parallel series of deep, circular indentations. Overlaying this was a fan-shaped swatch of grooves and runnels scratched in the sand, about six feet wide and also eastbound.

My footprints. The singular track of the walking stick held in my right hand. Just before sundown the night before, I had passed this way to fetch a load of dry kindling from the top of a white pine snag about a mile from camp. Half-buried in sand, the snag’s sun-bleached, wind-dried branches were polished as smooth as bones. The branches snapped easily in my hands. I tied them in a loose bundle with a frayed hank of yellow boat line scavenged from the beach. I dragged this bundle like a travois behind me. It left a curious track.

Then I noticed something else. Whatever trotted out of the woods last night intercepted my awkward trail. It stopped to sniff. Then it tracked me.

At this point, if I were telling a tall tale or writing a made for TV screenplay, the music would build ominously and I’d say I felt a shiver of fear run down my spine. What unknown beast was watching me from the edge of the woods? A north wind was building on Whitefish Bay, and the shiver I felt came from icy spray as surf pounded the shore. Maybe it was a frisson, too, at contact with something unknown, unknowable, and truly wild.

Could this really be a wolf tracking me? I tried to remember the wolf tracks I have seen in my life. When I was young and my eyesight better, I spent a summer above the Arctic Circle in the Brooks Mountains of Alaska. Wolves were not an endangered species there, and I saw tracks every day – in the dust on high ground, in the mud between sedge tussocks on the tundra, in fine glacial silt on gravel bars in the Koyukuk River. I found wolf sign wherever I went, but never saw a wolf. In recent years I’ve found tracks on the mud-packed berms of beaver dams at the western end of Lake Superior, distinct evidence of the famous wolves of Isle Royale. In every case, the tracks were dramatically different from dog tracks, both in size and shape.

Then I thought about what I have read about wolves. Michigan paid a bounty on their pelts as late as 1955, the year I was born, even though wolves had been exterminated for half a century in every corner of the state except Isle Royale. Despite the best predictions of wildlife biologists, though, wolves had made a discrete comeback in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. This wasn’t the result of some controversial wolf reintroduction program like the one in Yellowstone. No human intervention was required. The wolves did it all on their own in less than a decade. The winter before I found tracks at Whitefish Bay, more than 150 wolves in a dozen packs had been counted in the UP. Wolves had been spotted in every county there. So I could not use received wisdom and deductive reasoning to prove “wolf” was an impossibility.

West of the white pine snag where I gathered the kindling, I found the trail again. This time the tracks headed west after emerging from the woods. They looped gracefully from woods to water’s edge. The gait here was an easy trot. As I followed the tracks back and forth across the beach, I began to sense a pattern that I had never seen before at Whitefish Bay. It was the movement of a hunter. I imagined it doubling its chances of finding breakfast before sunrise, either a sleepy beaver in the swamp beyond the beach, or a spent salmon washed up on the shore. I followed the tracks this way for more than a mile, until the trail vanished finally in the woods near Pendills Creek.

The only mammal tracks on the beach between Little Creek and Pendills Creek, that day and for the next three days, were made by this unknown animal and me. I followed the trail again and again, reenacting the debate in my mind. When I walked east, toward camp, I thought it had to be a dog. When I walked west and sensed the rhythm of its running hunt between woods and shore, I felt it was a wolf. In a similar situation Henry Thoreau concluded, “Every man thus tracks himself through life.”

Since then I’ve thought a lot about this unknown animal. I’ve thought through it, to quote Peter Steinhart again. Here is the conclusion I reached. If it were a dog, it was a dog that remembered how and wanted to be a wolf. And if it were a wolf, it was edging like a dog toward the possibility of coexisting, warily, with humans. In either case, it was improvising on what we think to be the coded script for its species. In other words, it was improvising on its genome.

3.

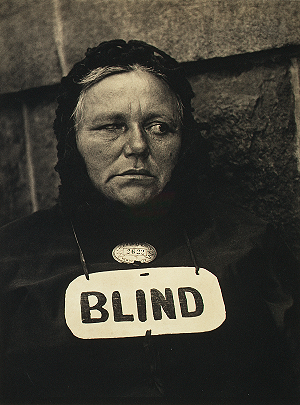

There are several reasons why I wanted to tell you this story. First of all, it gives you some sense of the phenomenology of my genetic disease, which is known in the medical literature as Stargard disease, a kind of macular degeneration. From my perspective, phenomenology is the key word here, not disease. I meet the criteria for being legally blind. My visual acuity is measured in terms of counting fingers at three feet. These objective facts don’t begin to convey my subjective experience in the world, which is very rich in what anthropologist Richard Nelson called “the raw material of the senses.” My experience of blindness is not filled with darkness, doom, and gloom. Unlike John Milton in his famous sonnet, I am not “light-denied” but light-drowned. My experience of blindness includes the use of some sight, mostly peripheral sight. Sometimes I think I confuse people who want me to fulfill some metaphorical category they call “blindness.” I try to tell them, on good days at least, that I will use whatever is left for as long as I have it. I also use memory and other senses to construct mental maps, like the hunter’s trail on the beach at Whitefish Bay, as I move through the world. I could call that improvising on the genome.

My story places me on the beach at Whitefish Bay for a very compelling reason. I think through places as well as animals, and this place is the heart of my sensory and spiritual landscape. I return to Whitefish Bay year after year like a migrating loon. I go there to renew myself. It is where I learned how to be blind by letting go of sight. It is where I feel most free, like that wolf or dog, to improvise new ways of being in the world. This underscores what is most fundamental in my experience of my disability: it may be genetic in origin, but its consequences are social. Absent most social constraints in a wild landscape like Whitefish Bay, I do not necessarily feel blind or diseased.

Here’s another reason for telling you this story, and this may be my most personal reason for traveling to NIH to talk with you: I want to complicate the usual subject-object relationship used in discussing genetic diseases and the people who carry them. It’s that darn phenomenology again. We tend to divide the world into subjects and objects. Scientists and health-care providers are the active subjects here, and the “victims” of genetic disease are the objects they act upon. In my story about Whitefish Bay, it’s hard to say who was tracking what. In the opening line about the princess and the frog, it’s hard to say who objectified whom. Life is complicated that way. That is an ambiguity, like the flaws in my genes, that I’ve learned to be comfortable with. I want you to know that a person with such a disease can claim subjective agency here, can make a place in the world and tell stories about it. That, too, is what I mean by improvising on the genome.

4.

There is one final reason for telling the story. It’s the speculative edge of what I am thinking and writing this spring, so it’s likely to come out as a question or set of questions rather than a conclusion. I hope we can get into it in our discussion. It has to do with evolution and what we want to control for our own useful purposes, and what we want to preserve beyond our control in the name of wildness.

AS you know, Charles Darwin began Origin of Species by talking about the human cultivation of domesticated species like the dog. He called this artificial selection, a conscious or unconscious process familiar to humans for thousands of years. With that as a givem, he proceeded to explain the evolution of wild species through the process of natural selection. Here is a wonderful quote:

It may metaphorically be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, the slightest variations; rejecting those that are bad, preserving and adding up all that are good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.

So, what was following my tracks at Whitefish Bay? A dog? A wolf? Was it the drive of evolution itself, looking for an opportunity? Or was it just my imagination, as the song goes, running away with me?

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

Pingback: After 150 Years, Charles Darwin’s Still Got My Back « a blind flaneur