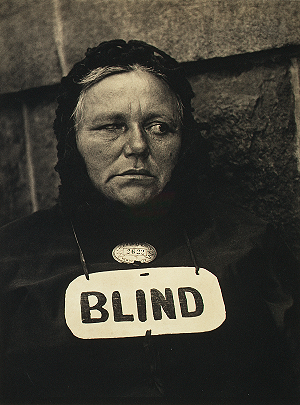

Bob Willis (left) with his helper Roy in the engine room of the City Products ice plant in Dayton, Ohio circa 1962.

My father liked to say with a sly twinkle, “I could weld two elephants’ asses together and make them stick… if you could make them stand still long enough.” Self-effacing humor was his style, not braggadocio. As often as not he lost himself in laughter before he ever reached the punchline.

He was a good welder. And carpenter. And plumber, pipefitter, electrician, mechanic and millwright. He was even a certified steam plant operator at the end of the Age of Steam. He was an industrial worker, though he never stood on a production line. He was one of the maintenance guys who kept the machines running. He told me once with Zen-like clarity, “When I walk into that plant every morning, I know something will be fucked up. That’s why I have a job.”

Bob Willis was a working man. Was he working class? I never heard him acknowledge that categorization. He mistrusted class distinctions of any kind. I do, too. That’s no surprise, as he set my moral compass in so many ways.

The working class label was everywhere in the 2016 election. Its cachet is likely to fade over time along with Donald Trump’s populist credibility. Before that happens, I want to explore what it means to be working class. It’s not as simple as the pundits, pollsters and political operatives think.

My father was a working man, and he was a Republican. He lived all his life in Ohio, except three years in Europe during World War II. His European experience is another story, a tangent I plan to follow in due course. For now, consider the demographic convergence: white working class Republican from Ohio, and a war veteran to boot. Had he lived to be 95, he could have met the gold standard for Trump voters this year.

I doubt it. More than once during the 2016 election, when it looked like the Grand Old Party was cracking up in fratricide under less-than-friendly fire, I thought about my dad and sighed, “They don’t make Republicans like him anymore.”

John Prine hit the nail on its head in the song “Grandpa Was A Carpenter”: “He voted for Eisenhower/’Cause Lincoln won the war.” My dad believed in Lincoln’s vision of equality in America, and he put his faith in Ike when he crossed the English Channel for the invasion of Normandy. He respected both Presidents’ pragmatism. He was a liberal Republican, if you can believe such an idea today. And he was not afraid to change his mind.

“I voted for Richard Nixon three times,” he told me after Watergate. “Now I know I was wrong.”

He wasn’t hoodwinked by Ronald Reagan, either. He mistrusted Reagan’s plan to scrap Social Security, and he openly opposed the Gipper’s military conspiracies in Central America. He’d become something of a pacifist by then. I remember his outrage after the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero as he celebrated mass in San Salvador. “We have no business getting mixed up with the kind of thugs who would do something like that.”

My dad had a heart attack in 1986. I visited him in the hospital on the day that news broke about the Iran-Contra scandal, in which the Reagan administration secretly sold illegal arms to Iran to raise money for anti-Communist guerillas in Nicaragua. Republicans selling missiles to the Ayatollah Khomeini – imagine that!

I told my dad about it in what turned out to be the last conversation in our conscious lives. He had other things on his mind. He shook his head knowingly and said just one word. “Bastards.”

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in