A talk by Mark Willis (2007)

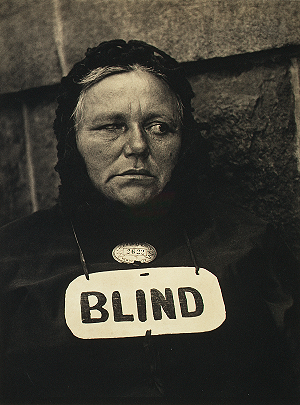

Paul Strand. Blind. 1916. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I want to find new ways to talk about accessibility to engage people who would not otherwise consider that it pertains to them. When I talk about accessibility it doesn’t mean whether or not there is wi-fi at Starbuck’s. It also doesn’t mean the larger context of accessibility for people with disabilities – whether or not there are wheelchair ramps or curb cuts. Those are examples of architectural accessibility. I am talking specifically about access to information and information technologies. I believe that what I will try to achieve in this discussion will relate to other, larger contexts in which we talk about accessibility. Ultimately, I want to talk about accessibility in terms of culture and cultural production.

This image by Paul Strand is my first milestone in talking about accessibility in terms of culture. It has haunted me ever since I first confronted it in the Paul Strand retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1990. The print is in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It has haunted me for several reasons. The first and most obvious reason is the sign that hangs around the woman’s neck. This is a photograph of a blind beggar taken on the street in New York City. As a cultural artifact, there are a number of interesting things about it. Just above the sign that pronounces the woman to be blind is a small pin with a number on it. That is her license number for begging. At the time, in the heyday of the Progressive Era, New York City required beggars to be licensed. It was an approach to managing society’s marginalized people by controlling them. If you wanted to beg on the street, you had to be certified. It’s not clear from the image’s historical documentation whether the city or the beggar herself hung the stigmatizing placard around her neck. To my eye, and particularly to how I remember the image, the placard and certification number are one and the same sign. It signals society’s distrust and its need to verify claims made upon its pity. It hearkens back to the myth of the Court of Miracles in 17th-century Paris, which we know best from Victor Hugo’s novel, Notre Dame de Paris. It reflects a deeply held cultural attitude about blindness and blind people that goes back much farther than that.

Another haunting aspect of this image is the way in which the photograph was taken. Paul Strand used a bulky 8”X10” large format camera. It was fitted with a trick lens with a right-angle mirror in it. This enabled the photographer to pose as if he were focusing on a fire hydrant or mail box rather than the photograph’s human subject. This was considered to be avant-garde photography in 1916. He managed to take candid shots of people on the street who had no idea that they were being photographed.

To me, that process is a kind of hiding. He certainly did not engage the subjects of his photographs. It reflects the ethical immaturity of Paul Strand as a young man and of photography as a young art form.

The image also haunts me as a piece of visual rhetoric that I want to appropriate for my own purposes.

In my experience as a visually impaired person who has to negotiate access to every conceivable form of printed information, from the gate assignments at the airport to the location of the men’s bathroom to the minutes of yesterday’s committee meeting… in almost every transaction in which sighted people simply read a printed text, I must negotiate access in one way or another. I’ve been doing this day in and day out for 35 years. In that time I’ve witnessed a lot of change in information technology and social attitudes about disability. Nevertheless, the most significant barrier to access for someone who self-discloses that she or he is blind is the stigmatizing gaze portrayed in Paul Strand’s photograph. It is the first and remains the greatest accessibility barrier.

My guess is, in the historical moment in which that photograph was taken, the social engineers who created the system for licensing beggars never imagined that that blind woman had culture or could make culture. She herself may not have believed that she could make culture. Paul Strand probably didn’t give her much credit for that, either.

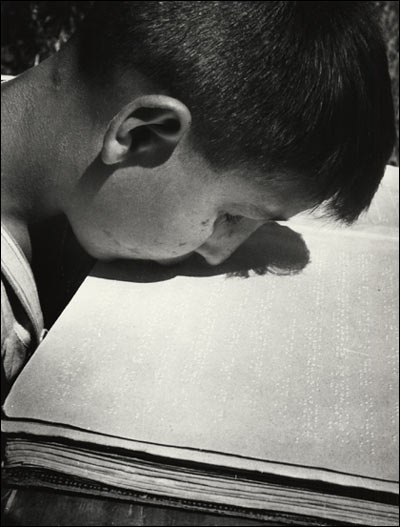

David Seymour. “Blind Boy Reading With His Lips”. 1948. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

This photograph could have been framed in a different way to milk much more pathos from it. The blind boy has no hands or arms. A civilian casualty of World War II, he was photographed at an Italian school where he learned to read braille with his lips.

David Seymour was better known by his French pen name, Chim. He was a pioneering photojournalist in the 1930s and later founded the Magnum Photos agency along with Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Brasson. Chim was known for his humanity and ability to establish the trust of his subjects, particularly the children he photographed. In 1948 UNICEF commissioned him to document the impact of war on children in Europe. This photo comes from that project.

This type of photojournalism is what I grew up with as a kid looking at Life magazine. It reflects a kind of socially engaged photography that fit into larger social projects — think of Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man. It expresses commitment.

Some people look at a photo like this and read into it a hero narrative. Here is a courageous disabled person who has an indomitable will to overcome adversity. I don’t see it quite that way. I believe the qualities of heroism and will to overcome are hard prescriptions to fill. That kind of hero narrative places too much responsibility on the individual rather than the individual in relation to society, which is a more authentic reflection of what the process of disability is.

Nonetheless, I look at this photograph and I still get charged by it. It means a lot to me. In the vocabulary of my visual rhetoric, it represents the process of making adaptations and negotiating accommodations. I truly believe that people with disabilities do this every day. Those adaptations and accommodations are a significant form of cultural production. This is one of my deepest convictions in a life of living with a disability, a life of working as a disability rights activist. Accessibility is creative work. It is not a band-aid or a pathway, something that must be done before one can have culture or consume culture. It is part of culture itself, in the same way that disability is part of the natural spectrum of the human condition.

Henry Butler. “Big Ol’ Kiss”. 2005. Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, New Orleans.

I present this image as an example of a blind photographer gazing back. The blind person isn’t the object of the gaze, but the active subject doing the gazing. The photographer said of this shot, “I always wanted to photograph Becky because she has a personality that is larger than life.”

When I look at this photo I can see some detail, but some I cannot. One thing I like about it is its ambiguity. I can’t tell whether this larger than life woman is indeed a woman or a man in drag. Either way, something is transgressed here. It clearly says New Orleans to me, and that’s all that really matters. New Orleans has a larger than life personality, too. That’s the New Orleans I love and miss.

Henry Butler is one of my most favorite New Orleans musicians. He’s a composer, recording artist, music educator, and steward of the piano tradition that begins with Jelly Roll Morton and runs through Professor Longhair and James Booker. He also is a blind photographer.

Butler has been taking photographs for more than twenty years. That goes back to the early time of optical cameras with auto focus. It certainly precedes digital cameras. I know of blind people who were experimenting with photography before auto-focus, when “F8 and be there” was prevailing wisdom. Focus is not really the point. Experimenting is the point. Curiosity is the point.

In a video that accompanied his 2005 photo exhibit at the Jonathan Ferrara Gallery in New Orleans, Butler explained why he began to take pictures:

I was always curious as to why sighted people looked at images and got so focused and intrigued by and enamored with images on paper or on canvas. So I decided I needed more than just an intellectual explanation for what I was either touching or realizing through somebody else’s eyes. I decided maybe I’ll just become a participant in capturing visual images.

From what he says about his process, I think Butler taps sensory skills for photography that are similar to those used in walking with a cane. He judges distances and makes decisions about aiming the camera and framing the shot. He engages his subjects before he shoots. When he says “personality” I think he means the salience of the subject standing before him.

What this image offers is a different way of looking at the social contract implicit in a photograph of another human being. It is completely different from the social contract in Paul Strand’s photo. Strand felt that he had to hide from his subject in order to photograph her. Butler needed to engage his subject in order to know where she stood.

That to me is participatory culture and social media at its most basic level. Blind people have been working in multimedia for years and years before the term was invented. The final point I want to make about blind photographers and participatory culture is this. It is not enough to simply have access to information. It’s not enough to simply consume media. Accessibility now needs to include the ability to create and transform information and media. It is driven by curiosity, and it needs to satisfy that curiosity.

In the interest of time, I reified the conclusion of this talk into a haiku. That was my exit strategy. The haiku reprised a rallying cry in the disability rights movement and the evolving field of disability studies: nothing about us without us.

nothing about us

without us no more hiding

enable engage

This talk was presented first at MiT5 in April 2007. Then it was titled Re-Imagining Accessibility in Participatory Culture. The working title now is “Curiosity & the Blind Photographer.” Please let me know what you think. Follow the blog thread

This talk was presented first at MiT5 in April 2007. Then it was titled Re-Imagining Accessibility in Participatory Culture. The working title now is “Curiosity & the Blind Photographer.” Please let me know what you think. Follow the blog thread

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

Pingback: a blind flaneur

“(Accessibility is) driven by curiosity, and it needs to satisfy that curiosity.” Very true.That is why I have gotten into photography just as my vision slid past the arbitrary line of blindness.

What tools are there and should there be and how can we bring them into being and disseminate? Is there such a thing as a run-on question?

Check out Blind Photographers on flickr at http://www.flickr.com/groups/blind_photographers/ or me at largeprintideas.blogspot.com (accessiblitly blot) or http://www.timobrienphotos.com (photography).

PS I saw your rant about accessibility of pdf files. I have pushed hard and mostly in vain to make latex (the math typesetting program used to write papers in lots of sciences) create tagged pdfs.

Pingback: a blind flaneur » MiT6: Stone & Papyrus, Storage & Transmission

Thanks so much for connecting to this talk, Tim (oberazzi). I welcome the addition of your links to this piece and the ideas explored here. When I put this talk together at the spur of the moment last year, I couldn’t find the blind photographers on Flickr. There is a long, digressive story to tell about what you find on Flickr when you search on “blind” but I won’t try to tell it here. I first found my way to the group through our mutual colleague lodrorigdzin. He found me via this blog and the subject of blind photographers. We are a small community with a truly global reach!

I hope to get involved with the group as I get a better handle on how Flickr works from the inside. I am less a blind photographer than a photo editor, something I’ve done in one capacity or another throughout 35 years in the media business. That career coincides with sweeping changes in the processes and tools of photography, publishing, and the phenomenology of my own eyesight. I’m still looking for the tools you ask about, and I expect to learn much from you and the community of blind photographers.

When I gave this talk at MIT, I made peace with PowerPoint. PPt had always been a barrier that I resisted and protested. Curiosity led me into learning how to use it for my own photo editing purposes. I’m following a similar process now with tagged PDF. I never thought I’d say this, but I’m trying to make peace with PDF now, too. Curiosity and creativity are the motives that bring me to the table.

Let’s stay in touch.

I look forward to learning more from and with you. When I first put together the Blind Photographers group, I tried to search flickr for other visually impaired members. It was a long, arduous process mostly, though not entirely, in vain. For the most part, members of our group have found their own way in, by accident as often as not, I would imagine. For this reason, I am looking to create other portals (in the traditional sense of entryway) to the group throughout the internet. The first step is our Best of Blind Photographers blog (bestofbp.blogspot.com), but hopefully there will be many more.

Pingback: Curiosity & The Blind Photographer | tim o'brien photos

Pingback: MiT6 Deadline Is Jan. 9 - Fair Use Lab

Dear Mark Wilis,

I’m enjoying enormously reading through your website.

i also wanted to tell you that your ‘Curiosity & the Blind Photographer’ piece led me to a thought for my own blog, http://pimlicokid.blogspot.com/

Every good wish

Barry Walsh

thank was an excellent read. I really liked how you put the images into context and helped me understand a different perspective.

Fascinating post. You’ve made me think new thoughts in a new way. Thank you.

Jafabrit, I was thrilled to find the street where I live has legs on the Internet via your Dayton Street art installation. Could I see it – or touch it – from somewhere along the sidewalk on Dayton Street?

Thanks, Melissa. I browsed Out Walking the Dog & will return for more. I have red-tailed hawks for neighbors, too. Coyotes stay mostly on the fringes of my village, but sometimes I hear them yipping when it’s quiet late at night.

Pingback: “Dark Light: The Art of Blind Photographers” - a blind flaneur