This was written for Tom on the August night in 1975 when the world learned of the death of Dmitri Shostakovich.

Letter to Tom Roberts

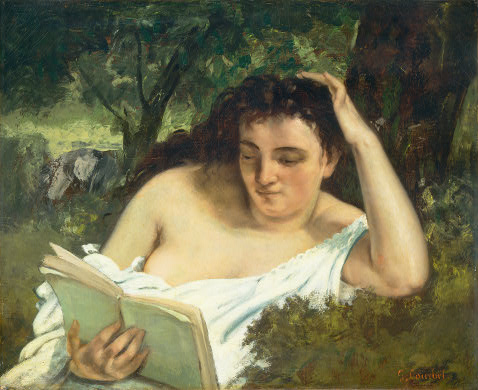

I stopped reading books. Is that possible?

My eyes hurt. My doctor says there are no

pain sensors in the eyes

so I can’t explainhow there are appetites so huge, too huge

for books or words, thinking, anything.

Everybody knows that and hopes

to find an appetite soon.Sometimes you have to do something drastic

slam something shut, books or eyelids

or you stretch a canvas just to rip it

apart, then listen.The cicadas are buzzing now. One theory

holds that cicadas are born with exposed brains

very sensitive to the elements, so much

sensitivity drives them insane with buzzing.This morning I heard the soft thud of an owl

dropping on a rabbit. I heard the clutch

of its talons, the animal gasp of breath, beating

wings then heat racing through food chains.According to Shostakovich, the revolution

ends in silence. Listen to the 1905 symphony.

After the snare drums — machine guns — after

the bass drums — the mass of running feeta fist beats inside a hammerless bell.

![gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day Gustave Caillebotte. Paris Street, Rainy Day (La Place de l’Europe, temps de pluie). 1877. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2009/02/gustave_caillebotte_paris_street_rainy_day_1877_wiki.jpg)

![Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com] Fog at Isle Royale [Source: wildmengoneborneo.com]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2008/04/isle_royale_fog.jpg)

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

If there is an emerging genetic underclass, I could run for class president or class clown. Read more in

Wow…that mysterious poem brings back layers of memories!

In the mid-1980’s, when living and working in NYC, I attended a concert at Carnegie Hall-Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony, “Babi Yar,” performed by the Montreal Symphony Orchestra and Men’s Choir. I had never before, nor since, heard such intense power in music. The snare drums, kettle drums, and a massive chorus of baritones contrasted with moments of complete silence.

During that symphony, I remembered and recognized that poem on another level.

The Babi Yar symphony is monumental music. It’s hard now to remember how the poem by Yevgeny Yevtuschenko, and Shostakovich’s setting of it, were dangerous acts of creative expression in the Soviet Union in the 60s. On a quieter scale, but no less poignant, is Shostakovich’s song cycle, “From Jewish Folk Poetry” (op. 79). In the grim “anti-cosmopolitan” campaigns of Stalin’s twilight years, DS risked his own seven grams of lead for composing it. My recording from 1952 features the master himself on piano, a haunting historical document. The music makes me think of Paul Celan’s famous assertion that poetry was impossible after Auschwitz unless it attempted to bear witness.